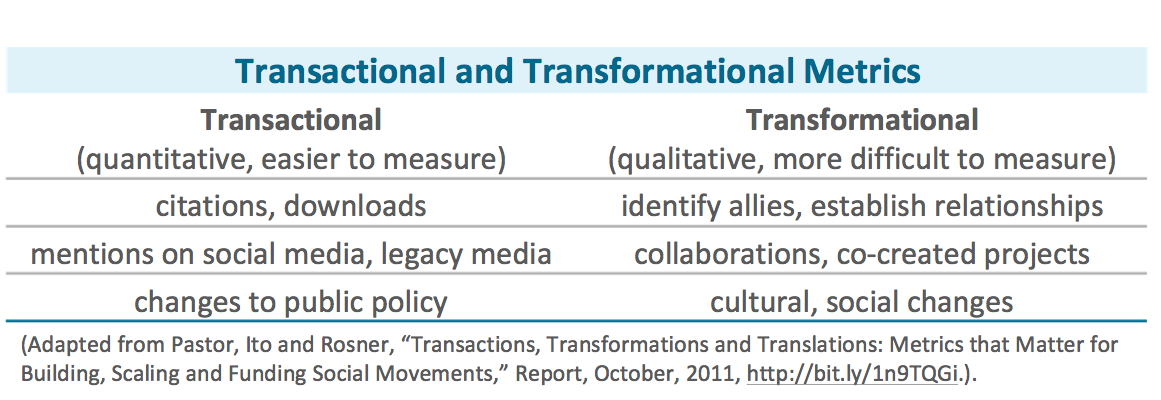

Our new series on scholarly communication continues with a look at the idea of “scholarly impact,” a topic we’ll feature regularly. The central issue at hand: how do we measure the value of scholarly work in a meaningful way?

In today’s Chronicle of Higher Education, Aisha Labi writes about the resistance among researchers in the UK to having the impact of their work measured. As Labi describes it:

The fundamental idea is relatively uncontroversial: As government spending in Britain has become more constrained, public investment in research must be shown to have value outside academe.

But calculating research’s broader value is a challenge—and a growing number of academics find themselves arguing that the requirements are unduly burdensome and do little to achieve their stated goals.

In the context of the UK, there is something called the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which requires that the impact of research by university departments accounts for 20% of the formula for financing them.

The resistance among UK academics, like Professor Philip Moriarty quoted in the article, is that while he sees his research in nanotechnology having a broad benefit to society, a focus on impact is a “perversion of the scientific method,” one that emphasizes “near-market” research, designed to generate a speedy economic return for taxpayers, he says.

I agree. If the definition of impact of scholarly work is going to be defined in business-school terms about ROI for taxpayers, then that’s not only a “perversion,” it’s a recipe for disaster for higher education as a long-term endeavor.

Resistance though there may be, some in the UK see value in the discussion of impact. The good folks at the LSE Impact of Social Sciences project are involved in a multi-year project to demonstrate how academic research in the social sciences achieves public policy impacts, contributes to economic prosperity and informs public understanding of policy issues and economic and social changes.

In the US, there’s a much different landscape of higher ed and impact is not (yet) tied to research funding in as systematic a way as in the UK with the REF. This doesn’t mean that academics in the US are uninterested in the impact of scholarly work, quite the contrary. There’s a long history of attempts to measure impact here.

How many inches?

The idea of measuring impact within scholarly disciplines has for most of the last century relied on counting the number of citations within peer-reviewed journals. For example, an individual scholar’s listing in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), which compiles number of citations in journals, has been a frequently consulted resource in tenure and promotion cases.

(Image source)

I know of stories in the olden days of analog when tenure and promotion committees would graduate student assistants to the library with an actual ruler in order to measure the number of inches a prospective candidate had in the SSCI. Sometimes a ruler is just a ruler, but is this really the best we can do in measuring the impact of our work?

Alternative Measures, or “Altmetrics”

Recently, attention in higher education has turned to new ways of measuring scholarly impact by incorporating the use of social media. The idea behind alternative measures, or “altmetrics,” is that the traditional metrics of citations in peer-reviewed journals (a la the (SSCI) should be joined by new measures, like number of page views, downloads, “likes” and re-tweets on social media. These have spawned a new generation of tools to automate the collection of this data into one platform or indicator (e.g., Almetrics,FigShare, PlumAnalytics, ImpactStory).

However, altmetrics are not yet widely used forms of measurement within academia by things like hiring committees or tenure and promotion committees. In fact, people in higher education don’t yet know what to make of these alternative measures and are actively working on how to resolve these issues. I, personally, sit on at least 3 committees within my institution and 1 committee in a professional association, that are all trying to come up with equitable, reasonable and widely understandable ways to measure scholarly work in the digital era.

Upworthy is Not the Same as Peer-Review

Many scholars express concern about the turn to social media as a measure of impact because of the kinds of information that often gets rewarded in an economy of “likes.” We might call this the “upworthy” problem. If you’ve ever seen this site, or been lulled into clicking on something there, there’s a kind of relentless cheeriness and warm, touchy-feelingness to all things shared on the site. People who want to endorse content there indicate that it is “upworthy,” meaning worth moving “up” on your pile of things to read and do online. But it’s hard to imagine most of the research I’m familiar with and admire ever getting a vote as “upworthy.”

In a recent piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Jill Lepore turned a critical eye to the problem of using social media as an indicator of scholarly impact. Lepore writes:

“…when publicity, for its own sake, is taken as a measure of worth, then attention replaces citation as the author’s compensation. One trouble here is: Peer review may reward opacity, but a search engine rewards nothing but outrageousness.”

Lepore is right to challenge us to think about what it is that search engines reward. And, I think it’s also critically important to reconsider the value we put in publishing writing that is opaque in journals locked behind paywalls with tiny audiences.

I think where Lepore, and lots of others, get the importance of social media for scholarly work wrong is when they assume that it’s all just “publicity” or self-promotion.

The reality is that many scholars are using social media so that they can have an impact on the world, not just on their peers in academe.

There’s a Whole World Beyond Academe

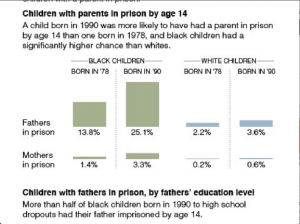

Many disciplines have traditions of talking about “impact,” but it’s usually in a negative context. I’ll pick on a couple of disciplines that I spend some time in. So, for example, sociologists are very accustomed to pointing out the negative impacts of social structures and policies on inequality. Scholars in public health and demography are all about measuring the impact of lots of things on “mortality rates” – a serious measure of impact if ever there was one. And, most social scientists of all stripes are perfectly fine with tracing worsening measures of inequality to changes in policy.

Yet, scholars are much less clear, timid even, on how scholarship might affect those laws and social policy.

This is especially ironic given what we know about what scholars want. According to a recent survey 92% of social science scholars said they wanted “more connection to policymakers.”

Are academics just not capable of thinking about their own impact on the world? I think we are because, well, because we’re human.

The Desire to Have an Impact is a Deep, Human Need

We all, as human beings, want to know that our life matters, that we had an impact. Many scholars, but certainly not all, want to know that the work they spend so much time, training, money and effort into matters in some way beyond the small circle of experts in their chosen field.

Martin Rees, an emeritus professor of cosmology and astrophysics at the University of Cambridge and one of Britain’s most noted scholars, quoted in the Chronicle piece mentioned at the top, says:

“Almost all scientists want their work to have an impact beyond academia, either commercial, societal, or broadly cultural, and are delighted when this happens. But they realize, as many administrators and politicians do not, that such successes cannot be planned for and are often best achieved by curiosity-motivated research.”

I think Professor Rees is right that most academics want their work to have an impact beyond academia. I don’t know that I agree with him that there’s no planning for it (more about that another time). The desire for our work to matter is a class-bound one, to be sure, in ways that may not be obvious. Sanitation workers have possibly the most important jobs from a public health perspective (much more important than doctors); they can certainly take comfort in the impact their job is having on promoting the health of large populations of people. It’s harder for academics, who trade in ideas, to point to the impact of our work, but I think that the desire is an existential one.

In many ways, the classic Frank Capra film, “Its’ a Wonderful Life,” (1946) is a film about impact. As you may recall, Jimmy Stewart’s character, George Bailey, on the verge of suicide, is given the gift of seeing what the world would have been like without him in it. A guardian angel, Clarence, replays key events in his life and then runs the reel of what unfolded because he wasn’t there. “Your brother died, George, because you weren’t there to save him when he fell in the ice,” Clarence explains. As he sees more and more of this alternative reality without him in it, George Bailey begs, “I want to live again,” and his wish is granted.

(Image source)

The moral of the film, of course, is that we all have a much greater impact than we realize on the lives of others. But it seems to be lesson that is lost on scholars and academics. Perhaps we are too practiced in the art of cynicism and critique to imagine that our research could have an impact.

The place where most academics I know are much clearer about their impact on the world is in the classroom. Academics will joke amongst ourselves about “shaping young minds,” but the joke reveals a truth we hold close: that what we do there matters. It can change lives. In many instances, we are academics because there was a scholar once, somewhere, who changed our lives, and then all we wanted to do was that… talk about ideas in ways that changed peoples’ lives. How do you measure a life? In cups of coffee, or in lectures given, in semesters taught.

Can We Work for Justice, Measure Impact, and Resist?

There are many reasonable arguments on the side of those who want to “resist metrification,” as my colleague Joan Greenbaum puts it. Governmental, institutional attempts to link research output to business profits are, to my way of thinking, wrong-headed and doomed to fail. We should, and must, resist efforts to use any form of measurement to surveil and discipline faculty in the service of economic gain.

But, I don’t think that’s the moment we’re in right now in the US.

I think that the moment we’re in is one in which academics are beginning to work in new, digitally augmented ways, and most institutions of higher education have no clue how to assess that work or evaluate the impact of a scholar who is up for tenure or promotion with a mostly digital portfolio.

I also think the moment we’re in is one of appalling economic inequality, and many, many academics I know want to join their work to the struggle to reduce that inequality. Mostly, they don’t know how to go about doing that. And, if they do go about doing that, they wonder: how will this work “count” for me when it comes time for hiring, tenure or promotion?

I think the moment we’re living in requires us to come up with innovative new ways to measure impact that take into account more kinds of work, including work for the public good. This is not as radical an idea as it sounds. I think we do this in some ways already.

When I write a tenure letter for someone to get promoted, I’m crafting a story about their impact on the world as a scholar, a teacher, and a member of a community. It’s very often the case that I will write about scholar up for tenure something like: “This scholar has made a profound impact on her/his community through their work engaging local residents about the topic of her/his research…” and then go on to detail the forms this impact has taken. Quite simply, a tenure letter is a way of crafting a story about impact.

We’re left with many questions about scholarly impact in the digital era. Most pressing for me is this rather grand question: How do you measure an idea that takes hold and changes peoples’ lives, changes public policy, and changes the way knowledge is created and shared?

I don’t think we know the answers to this question yet. We are still way before the beginning in understanding how to measure impact in ways that are meaningful.