Just about the worst thing you can say about a piece of sociological writing is that it’s “journalistic.” The term is often used as a criticism, interchangeable at times with “descriptive”, “thin,” or just plain superficial.

There’s good reason many us have little confidence in journalism: the closer a story comes to our own experience, the easier it is to see its flaws. Take, for example, the article about the proliferation of “hooking up” on college campuses that appeared in The New York Times a few years ago.

(Source: New York Times, “Sex on Campus”)

(Source: New York Times, “Sex on Campus”)

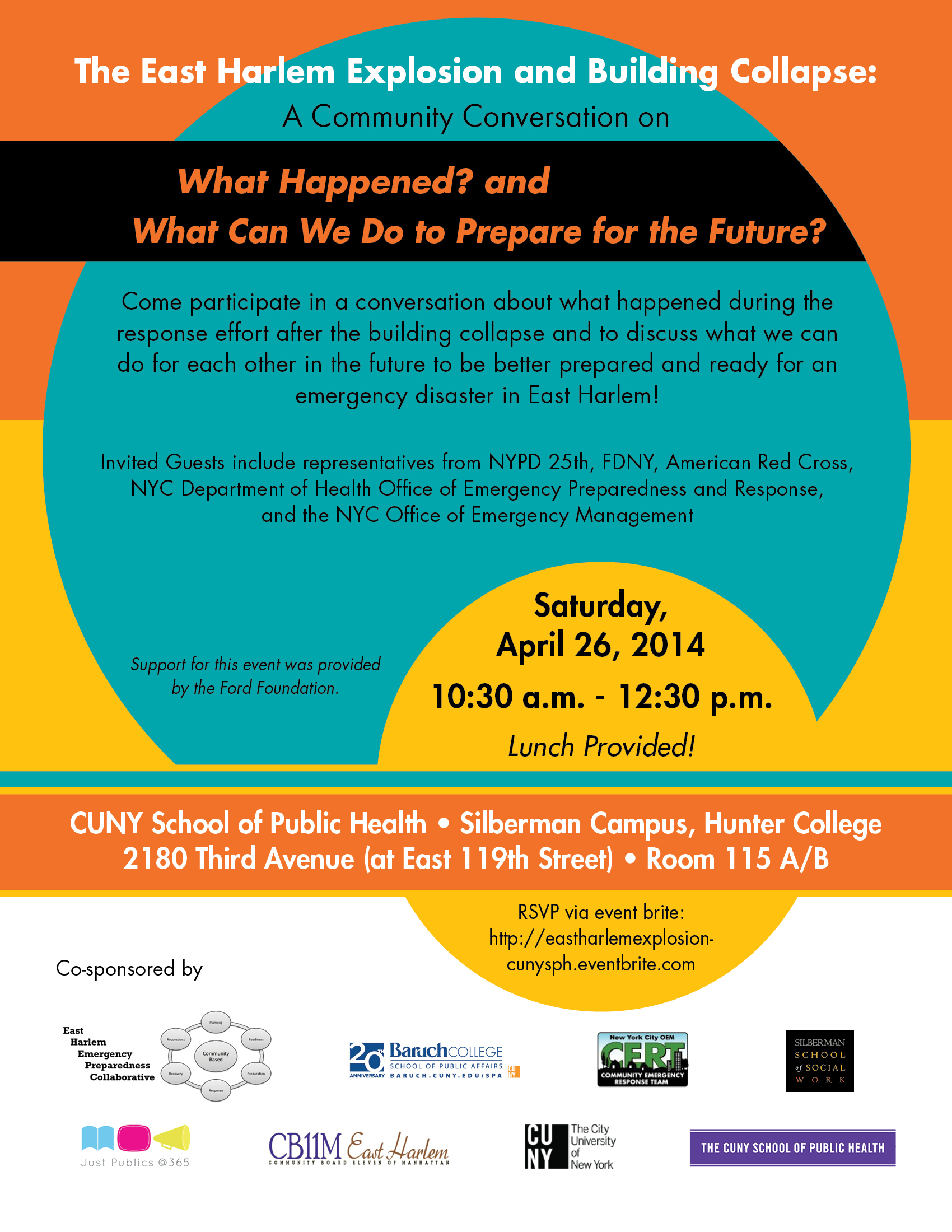

The story claimed that hooking up—sex outside of relationships—is commonplace on college campuses, and is being pursued as actively by women as men. On the basis of interviews with a small number of women at elite schools like the University of Pennsylvania, the article claimed that busy women students didn’t have time for full-blown relationships, so they opted for more superficial sexual liaisons.

It was quickly denounced by sociologists, who charged that the reporter based on claims on flimsy evidence. It was even more roundly criticized on the Internet by college students who felt that the article’s generalizations were unfair or inaccurate. Many of their classmates were indeed pursuing long-term relationships, some argued. A veritable cottage industry of commentary cropped up alongside the article, showing the press’ power to incite and engage. (See, for example http://goo.gl/vg57t.)

(Image Source)

(Image Source)

“Don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story,” journalists frequently joke. And in fact, for journalists, who must hook the reader in and keep their attention in order to hold onto their jobs, storytelling is an end in itself. Since their audiences are reading for the sheer pleasure of good writing, they write, at least partly, to entertain, and to encourage readers to keep reading.

This is how George Saunders, the award-winning author of nonfiction and short stories, puts it:

“I’m essentially trying to impersonate a first-time reader who has to pick up the story and at every point has to decide whether to continue reading.” If an “intelligent person picks it up, they’ll keep going. It’s an intimate thing between equals. I’m not above you talking down. We’re on the same level. You’re just as smart, just as worldly, just as curious as I am.”

Academic books, in contrast, tend to be written for a finite group of other experts, conveying an argument which is typically based on an extended research project. Writing a first book, which often emerges out of a dissertation, you may envision your audiences as particular professors on a tenure committee. Later on, you’re probably addressing experts in your field. While the writing should be persuasive, academics don’t particularly care if they’re holding the reader’s attention or not; they assume that what they say is inherently interesting, and that their potential readers are sufficiently intrigued by the topic to read on —even if the writing is less than scintillating.

Faced with these differences of purpose and audience, some would suggest that we leave storytelling to the journalists, and sociologizing to the sociologists. Let journalists speak to the people, while let sociologists keep working in the trenches, doing the hard work of data collection and analysis. As a graduate student of mine recently told me, “Sociology is supposed to be serious and scientific, not entertaining and story-like.”

Sociology and journalism, he was taught, are as different as cows and horses.

(Image Source)

(Image Source)

Early in their graduate school careers, students learn that professionalization means performing the role of sociologist, and differentiating oneself from those who value good writing for their own sake, and who write to entertain—writers of fiction and nonfiction. Rather than writing pleasurable prose, they are supposed to be advancing sociological knowledge.

But in fact, sociology and journalism have long existed in relation to one another. For one thing, sociologists know what they know partly through the media. And of course social scientists rely, at times, upon the media to disseminate our ideas to broader publics.

Likewise, journalists regularly mine sociological work for insights on everything from young adults’ changing pathways to adulthood, to the question of whether equality diminishes sexual desire, and sociologists are used to being consulted as experts for that telling quote on a variety of subjects. The best journalists do even more: browsing the web and journals for story ideas. They regularly raid our work, popularizing it for others to consume—at times without citing us.

Sociologists and journalists also have in common the fact that they’re both in the business of producing representations of social reality— stories– accounts of connected events that unfolds through time, which have characters that interact with another in different settings. Journalists and sociologists have different strategies of storytelling, to be sure. When journalists tell stories about social phenomena, such as hooking up on college campuses and other social trends, they tend to tell them through the lives of individuals—they show the reader what is going on, painting portraits of scenes and characters. Sociologists, in contrast, tell—they make arguments, drawing on data— numbers if we are quantitative sociologist, or vignettes and thick description if we are ethnographers.

But while we sociologists have been busy honing our rigorous methodological skills and ways of telling, we’ve ceded the field of translation, which requires showing, to smart journalists. By failing to discuss our work in compelling ways, we limit its impact, placing a wall, in effect, between our work and potential audiences.

Rather than deride “popular sociology” which addresses larger publics, in book-length works of general interest as well as shorter articles and essays –it’s time to reclaim it as something to aspire to. Popular sociology offers the general reader a sociological take on something he or she may be curious about. It embodies a hybrid style of writing, bridging journalism and sociology by showing and telling, painting a portrait of a group, a scene, or a trend that unfolds over time, offering thick description while analyzing what is occurring beneath the surface of events.

~ Arlene Stein is Professor of Sociology at Rutgers University, and editor of Contexts Magazine. You can follow her at twitter @SteinArlene. She blogs at https://steinarlene.wordpress.com.