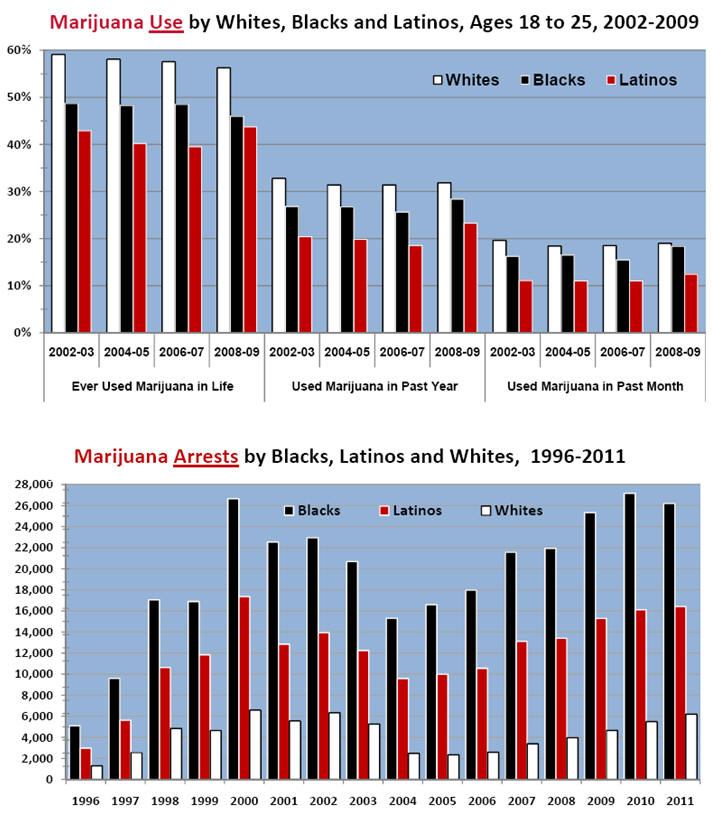

The first thing I learned about podcasting was that it is powerful medium. Podcasting is powerful not only because it has the ability to relate complex arguments into digestible bits of information, but also because it can transform those arguments into relatable stories. Rather than shoving statistics at an audience, podcasts can transform statistics about subjects (i.e. the number of people arrested in 2012 in the U.S. on nonviolent drug charges was 1.55 million) into stories about real people who felt the impact of those statistics. The unique ability of audio to highlight the experience of making knowledge can also connect listeners to scholarship in a way that books often fail to do. Podcasts can allow academics to infuse themselves into the arguments they make rather than downplay their connection to their scholarship.

Podcasts – meaning audio uploaded to iTunes – are just one way to use audio to connect with a wider audience. There are many other platforms including WordPress, SoundCloud, and MixCloud that allow you to share audio. Often, these non-iTunes venues allow for a stronger engagement with your audience because they allow users to post comments on audio files. And, depending on your resources, posting at all four of these venues can give you the most engagement.

Making a good podcast requires planning. A podcast posted on iTunes should have a consistent length, release time, and theme to be successful. In other words, if you want a create a weekly interview-based topically connected 15 minute podcast series, iTunes is probably the most powerful platform to gain a strong following. On the other hand, if you want to post interviews sporadically and have audio that varies in length and topic then something like SoundCloud or your own personal WordPress site would probably gain more traction.

Not all good audio projects have to be formatted like a podcast. Projects can vary in length and subject but use the same intro and outro to make the audio files cohesive. For example, the JustPublics@365 Podcast Series uses the same music intro and outro for every episode. We also use that slice of audio for our shorter audio projects that we post exclusively to SoundCloud.

Collecting audio does not have to be expensive, but it can be. Like most media projects, you can make podcasts as expensive or inexpensive as you want. SoundCloud has the hefty price tag of $121.50 per year to upload an unlimited number of tracks. Using services like BuzzSprout, which offer podcast hosting can cost between $12 and $24 a month. You can upload audio to a server and link that file in a post in your WordPress site. Audio files take up a large amount of room so, often, you will have to pay for some type of server space.

You can be scrappy with equipment. Smartphones have the ability to record surprisingly excellent audio. iPhone apps like Voice Recorder HD ($1.99) or the built in Voice Memos can give you high quality audio. If you want to have higher quality audio you can purchase a number of different microphones that plug directly into your computer (I like the Apogee Electronics MiC Studio Quality USB Microphone) or that plug right into your iPhone or Android (I like the Rode SmartLav or the iRig MIC Cast).

Editing can make all the difference. You can use a number of different programs to edit your audio. GarageBand is one of the easier ways to learn to edit your audio. You can record directly into GarageBand or import audio from prerecorded files. It is free to Mac users so it is a great option for beginners. Audacity is free, open source, cross-platform software for recording and editing sounds that is compatible with PCs and Macs. It is slightly more clunky than GarageBand, but is an equally effective way to edit audio.

Length is up for debate. There are ongoing debates about how long a podcast should be. Some say 3 minutes, some say 30 minutes. I say, the most important thing is to pick a length and stick to it. If your audience is engaging with 30-minutes of content, there is no reason to switch to a 3 minute format. On the other hand, if you are making 30-minute podcasts and no one is engaging with them, it may be time to rethink your strategy.

There are many different types of podcasts. One powerful way to weave stories for listeners is through audio interviews. The podcasts and audio that I have produced for JustPublics@365 have mostly consisted of these. I think interviews are most effective when combined with “on the ground” audio, but they can also be powerful in and of themselves.

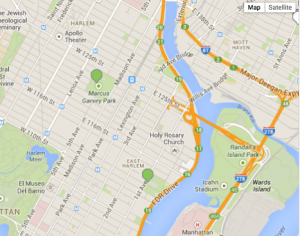

When JustPublics@365 interviewed people affected by the East Harlem Building Collapse the interviews were edited to have the same intro and outro for every interview in addition to the same music from the JustPublics@365 Series.

Community Conversations – East Harlem Resident Sam Goudif

This method of interviewing consisted of asking the interviewee a series of questions to get them primed for the interview and then recording their uninterrupted story from start to finish. When editing these interviews, I inserted myself only in the beginning and end in order to give context to the story.

When creating the JustPublics@365 Podcast Series, I took a different approach and included my questions in the produced audio. This interview style podcast involved in-depth research and thought out questions, which I shared with the interviewee before the interview. These podcasts are structured in a way that allows for replicability and their format is designed for a structured ongoing series.

Podcast Episode 1 – Michael Fabricant and Michelle Fine

The most important thing is consistency. However you decide to structure your podcast, you should be consistent and stick to your strategy!

Heidi Knoblauch (@heidiknoblauch) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the History of Medicine at Yale University and JustPublics@365’s program coordinator.