The rate of women who are incarcerated, whether in prison or jail, is increasing. According to the ACLU, more than 200,000 women are currently in jail or prison, and another 1 million are under the control of the probation and parole system.

While many of the demographics for women in prison parallel those of men – that is, they are disproportionately black and poor – a closer look reveals another story. Women bring a gendered life experience with them to incarceration. And, being gendered ‘woman’ in this society often means a series of difficult life circumstances and hardships, like physical or sexual abuse in childhood or as an adult. Incarceration places the additional burdens of isolation, humiliation, and systemic marginalization to these gendered life experiences.

It is precisely because of their gendered life experiences prior to incarceration that women need gender-based interventions in order to re-enter their communities and rejoin their families.

National Profile of Women Offenders

A profile based on national data (NICIC.gov: “Gender-Responsive Strategies”) for women offenders reveals the following characteristics:

- Disproportionately women of color.

- In their early to mid-30s.

- Most likely to have been convicted of a drug-related offense.

- From fragmented families that include other family members who also have been involved with the criminal justice system.

- Survivors of physical and/or sexual abuse as children and adults.

- Individuals with significant substance abuse problems.

- Individuals with multiple physical and mental health problems.

- Unmarried mothers of minor children.

- Individuals with a high school or general equivalency diploma (GED) but limited vocational training and sporadic work histories.

One in three

One can hardly talk (intelligently) about women in prison without talking about childhood trauma and physical and sexual abuse.

Earlier this year, the Correctional Association of New York – a 170-year-old advocacy organization that leads efforts to protect and advance the rights of incarcerated women and their families – published the following facts about women and the criminal justice system:

- At least one in three girls in the United States is sexually abused by the time they reach the age of 18.

- Women in prison are twice as likely as women in the general public to report childhood histories of physical or sexual abuse.

- Nationally, more than 37% of women in state prisons have been raped before incarceration.

- 90% of women incarcerated at Bedford Hills reported suffering physical or sexual violence in their lifetimes.

- 82% of women at Bedford Hills reported having a childhood history of severe physical and/or sexual abuse.

Yet another casualty of the war on drugs, most women are behind bars because of non-violent drug-related offenses. Much of their substance abuse is generally understood as “self-medication”, a device to help them cope with the aftershocks of traumatic childhood experiences – such as, in many cases, parental incarceration. In addition, the flood of crack cocaine that hit urban areas in the 1980s increased women’s experience of another kind of sexual trauma, street-level prostitution – a mainstay survival strategy for women addicts along with low-level drug dealing and petty property crimes.

The recent case of Marissa Alexander, sentenced to 20 years in a Florida prison for firing warning shots into the ceiling in an attempt to fend off her abusive husband, brought the national spotlight to the fate of many women who dare defend themselves and their children from their abusers. Marissa’s appeal was successful and she has been granted a new trial – although she has been incarcerated since 2010. The Correctional Association has been spearheading the campaign to pass the Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act, which would change New York State laws that require long, harsh sentences for survivors who protect themselves from an abuser’s violence.

Impact of Incarceration on Children, Families

Attorney General Eric Holder’s recent declaration that “too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long, and for no truly good law enforcement reason” has drawn public attention to the issue of mass incarceration. One area that still needs even greater attention is the impact that incarceration has on children and families.

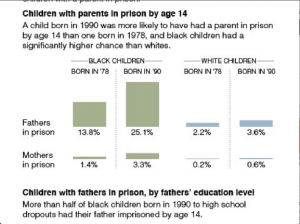

(Sources: Christopher Wildeman, “Parental Imprisonment, the Prison Boom, and the Concentration of Childhood Disadvantage,” Demography, May, 2009; and The New York Times, July 4, 2009)

Over 2.3 million children in the United States currently have a parent who is incarcerated in the jail or prison system and over 10 million children have experienced parental incarceration in their lifetime. The social and health risks and outcomes that parental incarceration has on children include increased stress, family disruption, feelings of abandonment, traumatic separation, loneliness, stigma, unstable childcare arrangements, strained parenting, reduced care giving abilities upon reunification, and home, school, and neighborhood moves.

Visitation with children in prison is not an option for most mothers in prison for the duration of their time behind bars and, on average, the children of incarcerated mothers will live with at least two different caregivers during the period of their incarceration. More than half will experience separation from their siblings.

Upon release from incarceration, reuniting with the incarcerated parent with his or her children is often desirable; however, the actual impact of the reunification process on children and families merits further investigation. Reunions often causes stress to both parent and children because for better or for worse it constitutes a disruption of the status quo, and as such demands that both adults and children adapt to new household dynamics, especially if children had previously been placed in foster care. Bonds broken by incarceration are not easily mended, and children may experience difficulty in forming meaningful attachments for the rest of their lives.

Generally lacking adequate job skills, most women have trouble supporting a family upon their release from prison, and the communities to which they return are unprepared to receive them. And after serving their time, a woman’s criminal record may bar them, through law or practice, from accessing vital resources, such as employment; public housing; welfare benefits; food stamps; financial assistance for education. These post-conviction penalties constitute an ongoing and self-perpetuating additional layer of punishment that endures far beyond their prison sentence.

Designing programs for impact

According to the Women’s Prison Association, programs aimed at supporting women returning from prison must take account of the family responsibilities women bear. Programs should be designed with the understanding that women and their families are often burdened with conflicting and inflexible requirements of multiple agencies. Criminal justice, welfare and child welfare agencies may set competing or conflicting goals and conditions for women, while limiting or denying access to essential services needed to stabilize and maintain the family unit.

(Image credit: Michael Kirby for The New York Times)

(Image credit: Michael Kirby for The New York Times)

Family-focused Alternative to Incarceration (ATI) programs such as Drew House in Brooklyn, NY, have been successful at providing selected women charged with felonies and their children with the tools and the chance to strengthen these families without compromising public safety. However, the need to collect and coherently use women-centered data when addressing incarcerated women remains crucial for the relevance and success of any intervention.

~This post was co-authored by Alice Cini and Stephanie Hubbard. Alice Cini is a social justice advocate and Social Work Fellow at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s From Punishment to Public Health Initiative. You can follow her on Twitter @CinikAl. Stephanie Hubbard is a public health professional and advocate for youth and humans rights at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

***

This post is part of the Monthly Social Justice Topic Series on From Punishment To Public Health (P2PH). If you have any questions, research that you would like to share related to P2PH or are interested in being interviewed for the series, please contact Morgane Richardson at [email protected] with the subject line, “P2PH Series.”