Data Visualization of Activist Lesbian-Queer Histories

Activist history is especially important to lesbian and queer women because it is this marginalized group’s primary public, visible history. Data visualization tools can help us understand that history.

My research looks at the lives, spaces, and experiences of justice and injustice of lesbians and queer women in New York City from 1983 to 2008, a span of time marked at the beginning by AIDS activism toward the end by the popular cable tv show “The L Word” and asks: did these women’s lives get better? If so, how important was activism to this? Part of this answer is in the archival data of lesbian and queer women’s activism.

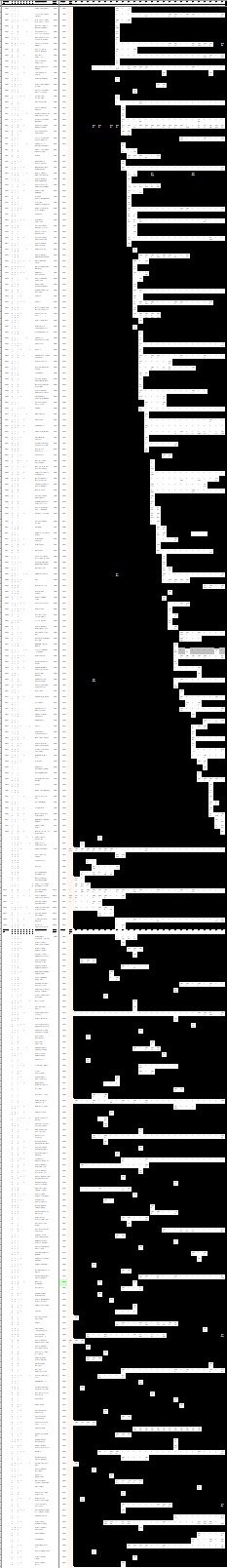

Originally part of my dissertation research and now a part of the series of books I am writing, I knew the activist and organizational history was much more complex because I surveyed the complete collection of 2,300+ organizational records at the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA). Out of that, I created a data visualization (see left) of all NYC-based organizational records spanning my period of study, 1983-2008 (n = 381).

My choice of data visualization as a tool was inspired by a conundrum: how do you make sense of 25 years of radical and mundane social, sexual, political, and cultural history in nearly 2,000 detailed nodes of information spanning a word to a paragraph to a few pages each?

The minutiae of politics, places, and people’s everyday lives was available in the stories of lesbian and queer organizational records and publications in ways that weren’t accessible through other research methods, like the focus group interviews I used in another part of the research. Rather than the individual stories that emerged from personal interviews, an entire chronological history of lesbian-queer life could unfold in the quantitative study of these places, spaces, and people.

This is where data visualization came in. I had read Nathan Yau’s utterly inspiring Visualize This when it came out but never dug in to data visualization and didn’t know how it might be useful for my research.

Attending the MediaCamp workshop on Data Visualization with Amanda Hickman was a breakthrough for me. In that workshop, I realized that the only way my data from the LHA would be revealing and fun was through data visualization. Using the data visualization tools HighChartsJS and jsFiddle, in just a few hours I saw the way my data shifted from 2D to a 3D platform for the public. These tools made my data about activist lesbian and queer women suddenly interactive and engaging in ways I had not imagined.

Here’s an example. One of the key takeaways from my focus groups with lesbians and queer women who came out between 1983 and 2008 was the persistence experience of loss and mourning of key lesbian-queer places, namely neighborhoods and bars, as well as bookstores and other community spaces. At the same time, many women, especially those who had come out in the 1980s and 1990s generations, lived with an expectation that one just created the organization or space they required, often through activism or socializing. When we turn to the actual numbers of lesbian and queer organizations in terms of their totals and their patterns of opening and closing, there is more to these shifts.

The generational social and political shifts explain a great deal about the growth of these organizations and this helps to frame my reading of this visualization. The number of activist lesbian-queer organizations rises significantly in the 1980s and early 1990s, as we can see in the graph above, both in terms of the total and those founded. Many of these groups were inspired by the continued to response to issues facing women and the successes of the feminist movement, as well as the burgeoning and powerful response to the AIDS crisis and the inspiration for change instilled by many movements for action.

There are also outcomes for organizing in the 1980s and 1990s that this graph also illustrates. Prior to this time period, there were very few if any social support services especially for LGBTQ people at the state or national level. During rhis period of activism there was a pattern of growth in the non-profit industrial complex as a primary method of social support for LGBTQ people in the US. In the 2000s, the number of these groups plateaued. This matches the ways non-profit organizations have become the official brokers of what remains of the US welfare state as it relates to LGBTQ concerns.

The LHA records have more to say on a range of issues relevant to lesbian and queer women. In a series of posts on my site, I’ll be posting a set of interactive data visualizations from my analysis of the 381 NYC-based records available at the LHA of lesbian and/or queer organizations spanning 25 years (1983-2008). I invite you to join me in exploring the meaning behind an often invisibilized activist lesbian-queer past.

~ Jen Jack Gieseking, PhD is a cultural geographer and environmental psychologist. Her website is jgieseking.org.