Join JustPublics@365 for the Information Interventions @ CUNY series:

Share It Now or Save It For Later:

Making Choices about Dissertations and Publishing

Thursday, May 1, 2014

2-4 p.m.

Graduate Center Room C198

Join us for a lively panel debate on the sharing versus embargoing of dissertations and theses. We’ll explore the pros and cons of this nuanced issue with a panel including representatives from Columbia University Press, Penn Press, and the Modern Language Association, as well as recent GC alums who made different choices about their dissertations. (We’ll also tell you how to change your embargo settings if you’ve already deposited!)

Should you put your work in a secret bunker?

Photo is © marcmo, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license.

Our panelists:

- Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Director of Scholarly Communication, Modern Language Association

- Philip Leventhal, Editor for Literary Studies, Journalism, and U.S. History, Columbia University Press

- Jerome Singerman, Senior Humanities Editor, University of Pennsylvania Press

- Gregory Donovan, Assistant Professor, Sociology and Urban Studies, Saint Peter’s University and Graduate Center Alumnus

- Colleen Eren, Assistant Professor, Criminal Justice, LaGuardia Community College and Graduate Center Alumna

- Polly Thistlethwaite, Chief Librarian, Graduate Center (Moderator)

Background:

Last summer, the American Historical Association made headlines when it issued a statement encouraging universities to allow their history Ph.D. graduates to embargo, or keep private, their dissertations for up to six years, claiming that “an increasing number of university presses are reluctant to offer a publishing contract to newly minted PhDs whose dissertations have been freely available via online sources.” Meanwhile, a survey of scholarly publishers revealed that a majority of university press editors are happy to consider proposals for books based on open access dissertations. And the executive director of the Association of American University Presses reported, after talking to the heads of 15 university presses, “I haven’t found one person who has said if it is available open access, we won’t publish it.”

These statements generated a raging debate that has left many graduate students unsure of their options and unsure how to proceed:

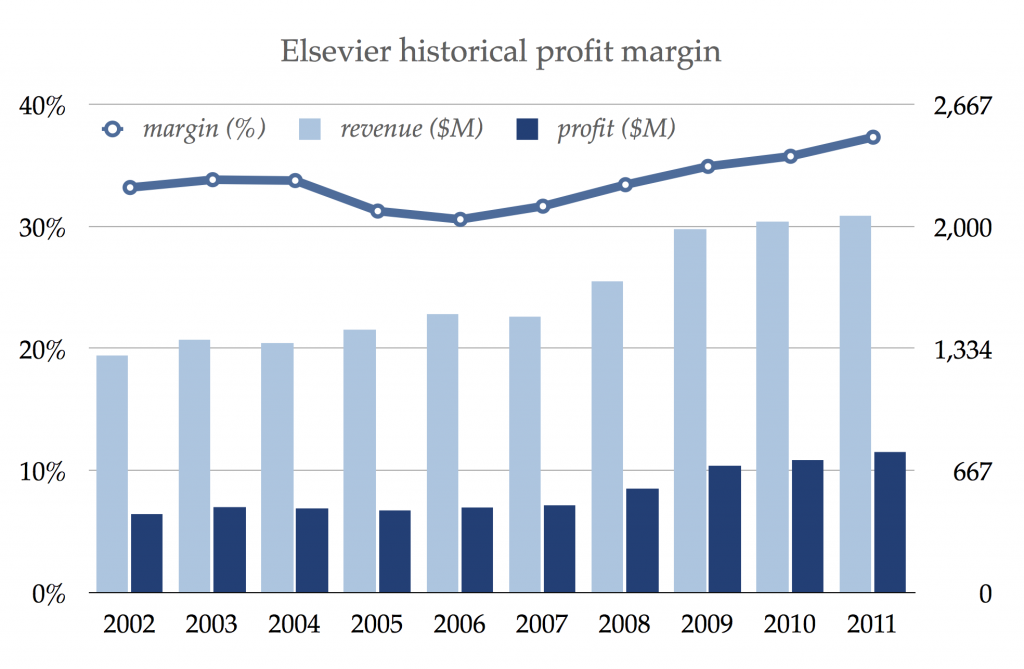

- Are open access dissertations really less likely to be published as a book? Or are they more likely to be found, read, and responded to, thus demonstrating to book publishers their appeal and marketability?

- Just how similar is a dissertation to a book, anyway? How much does it change between graduation and publication?

- Is the real problem tenure and promotion committees that expect applicants to have authored scholarly books, which, as the landscape of scholarly publishing evolves, seem to be increasingly difficult to publish? Do they need to adjust their expectations in response to current publishing realities?

- Do universities have a responsibility to share with the world the research produced in their graduate programs? Are long embargoes antithetical to scholarly values? Do they hinder disciplinary advancement? How long is enough?

- And where does this leave graduate students — in all disciplines, not just history or the humanities? Should they make their dissertations and theses open access, or should they embargo them — and if so, for how long?

Details and how to register:

Light refreshments will be served.

Space is limited! Please RSVP by April 23.

This event is co-sponsored by the Office of Career Planning and Professional Development, the LACUNY Scholarly Communications Roundtable, the Graduate Center Library, and Just Publics @ 365.

Reposted from the Graduate Center Library Blog https://gclibrary.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2014/04/04/share-or-save/