Nick Kristof, columnist for the New York Times, published an op-ed on Sunday pointing out the need for professors in the public sphere. His criticism is basically that most academics are not engaged in ‘today’s great debates’:

Some of the smartest thinkers on problems at home and around the world are university professors, but most of them just don’t matter in today’s great debates.

The most stinging dismissal of a point is to say: “That’s academic.” In other words, to be a scholar is, often, to be irrelevant.

Lots of academics immediately jumped on Twitter using the hashtag #engagedacademics (still going strong) and let Kristof know what they thought he got wrong, primarily that many of us are (already) engaged and we’re doing it through Twitter. Kristof replied via his Facebook page, saying (in part):

One objection is that in fact there are lots of professors on Twitter. Sure, but there are 1.5 million professors in America, and not nearly enough throw themselves into public engagement.

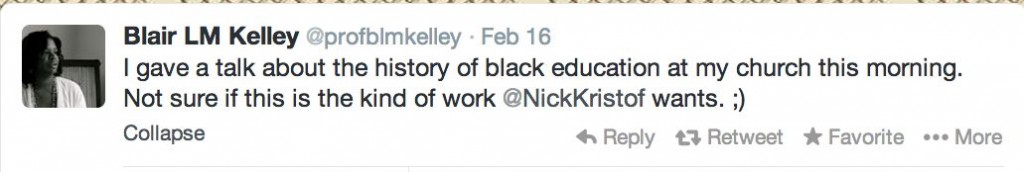

Basically, the Twitter critics of Kristof came down around a ‘cast a wider net for how you define engagement’ argument, such as this comment from Professor Blair Kelley (@profblmkelley):

The print edition of the New York Times has the letters to the editors they selected to respond to Kristof (I see mine didn’t make it), with a range of critiques suggesting:

- more user-inspired, policy-relevant research (Gromes),

- cast a wider net for defining engagement (Sugrue),

- change the outputs of scholarly research to include forms intended for public audiences (Iglesias)

- this is an old attack on academics and is anti-intellectual (Steinberger)

- think tanks are the answer, though even think tanks have a hard time finding academics who can speak to a broad audience (Selee).

A number of #engagedacademics took to longer-than-140 blog post form to post their critiques of Kristof. Here’s a roundup of what they had to say, organized very broadly by key arguments (of course, many posts make several arguments, so please do read the linked posts for more nuance than this bulleted list summary).

What academics need is more online navel-gazing:

- Chuck Pearson, started the hashtag #EngagedAcademics, and explains at some length, why he did.

This is an old criticism:

-

Sarah Chinn, The Public (Anti-)Intellectual : But beyond the specifics of whether academics do or don’t have anything to say in the public square, I’m more interested in the theme itself, which seems to reappear every now and then. In a nutshell, it’s this: oh you eggheaded academics! Why can’t you talk to the common person about interesting things? This is hardly a new development. Richard Hofstadter wrote the groundbreakingAnti-Intellectualism in American Life in 1966, for God’s sake, and he traced complaining about people who think they’re smarter than everyone else back to the very beginnings of the American Republic.

-

Pat Thomson, academics all write badly..another response to a familiar critique: In the UK context, Kristof’s argument seems like a very cheap shot indeed. Another go at academics for being obscure and difficult. Yes, we all write the odd arcane paper and yes, it is rewarded and yes, it might only be read by three people. But we also try really hard to write other things too. Today’s academic writes and publishes for a range of audiences. What’s more, and by the way, I thought mentally wagging my finger at Kristof, the UK academy and the public are not as easily cut apart as that.

It’s the reward structure:

-

Austin Frakt, “Publish and Vanish”: academics are generally not directly rewarded professionally for translation and dissemination work, particularly via new and social media. Promotion and tenure is usually based on number and prestige of scholarly publications, classroom teaching, and “service” (e.g., roles on institutional committees). Of these, publishing is the most uncertain and angst-ridden process. “Publish or perish,” is a familiar characterization. But, if by publishing only in obscure academic journals, one disappears from broader, public view, perhaps we should say, “Publish and vanish.”

-

Syreeta, UofVenus/Feministing: Above all, his column and subsequent blog post just seem so out-of-touch with the machine of the academy. There are real-life economic interests that drive our intelligentsia towards publishing “gobbledygook…hidden in obscure journals,” which are inextricably linked to a very powerful interest by said academics in securing full-time employment. People need jobs, my dude! And publication is a critical motivator and performance metric for the academic seeking tenure at any private or public institution. Compounded by the rising cost of tuition and the painful underfunding of scholarly research (the social sciences in particular), these spots for long-term employment are coveted; in March, a vote led by Senator Coburn barred funding for scholarly research in political science that doesn’t promote national security or economic interests. Colleges cut tenure lines for departments with a frequency that I’m not able to quantify. Add as a multiplier the growing adjunct specialized labor underclass, highly competitive and woefully underpaid posts for emerging academics seeking entry into the academy, who also have to write and publish to gain visibility and survive.

-

Christine Cheng, Academia and Incentives: The core problem is one of incentives within academia: Academic prestige/tenure/promotion is based purely on publications. On the surface, this seems like a fair way of gauging merit. But it means that everything else that professors do tends to run a distant second (teaching, administration and service, public engagement). Given the fierce competition for academic posts these days, no one is going to give up their research time for public engagement (unless s/he enjoys doing it if they don’t already have tenure.

-

Stephen Manning, Transforming Academia: There might be another, underutilized way of making academia more progressive and impactful: hiring and promotion policies. Many of us scholars are involved in recruiting new PhD students and faculty every year. And oftentimes – let’s be honest – it comes down to a simple question: can this person publish or not? It should be obvious that this selection mechanism will reproduce the very mindset that prevents academia from making a more important impact in this world. Instead, I propose that hiring should be guided by: academic interest, mindset and experience outside academia.

-

Janet Stemwedel, Scientific American: “…ignores that the current structures of retention, tenure, and promotion, of hiring, of grant-awarding, keep score with metrics like impact factors that entrench the primacy of a conversation in the pages of peer-reviewed journals while making other conversations objectively worthless — at least from the point of view of the evaluation on which one’s academic career flourishes or founders.”

I would, but I’m teaching four classes (variation on reward structure):

-

Laura Tanenbaum, Jacobin: As one of those professors teaching four classes at a community college, I do wish I had more time for my (perfectly lucid if I may say so) writing, but I also have a crazy idea that teaching hundreds of working-class, immigrant, and first generation college students every year might be a way of serving the public. I didn’t realize the only way to do that was to be a consigliere.”

We’re already here (variation on ‘cast a wider net’):

-

Erik Voeten, MonkeyCage: Yet, the piece is just a merciless exercise in stereotyping. It’s like saying that op-ed writers just get their stories from cab drivers and pay little or no attention to facts. There are hundreds of academic political scientists whose research is far from irrelevant and who seek to communicate their insights to the general public via blogs, social media, op-eds, online lectures and so on. They are easier to find than ever before. Indeed The New York Times just found one to help fill the void of Nate Silver’s departure. I am with Steve Saideman that political scientists are now probably engaging the public more than ever.

-

Erica Chenoweth, A Note on Academic (Ir)relevance: This is the part that surprised me the most about Kristof’s article: the supposition that our work is only relevant if it directly influences “important people.” But what if one’s work speaks to people outside of these traditional halls of power? Is such impact irrelevant? For example, many sociologists, whom Kristof writes off as a bunch of radicals who are hopelessly lost of any relevance, tend to be quite engaged with the problems of our day — just not in the way Kristof seems to privilege. Just check out Sociologists without Borders, or different proponents of applied sociology, and you will find that many sociologists work tirelessly (and often without compensation) to draw on the insights of their work to improve the lives of ordinary people.

Kristof things the category ‘public intellectual’ is only for white dudes:

-

Raul Pacheco-Vega, Challenges of Public Engagement for Marginalized Voices: he reason that prompted me to write this post was the repeated process where the pieces most retweeted and engaged upon (even by Kristof himself) were those of white males. You could always say that it was only those academics who took it upon themselves to write a piece in response, and I’m grateful that they did. But there were several women who wrote very smart take-downs of Kristof’s column, and I saw less conversation and publicizing of those while I followed the conversation on Twitter.

Marginalized people are to be saved, not speak for themselves:

-

Corey Robin, Look Who Kristof’s Saving Now: I don’t ever expect Kristof to look to the material sources of this problem; that would require him to raise the sorts of questions about contemporary capitalism that journalists of his ilk are not inclined—or paid—to raise. But Kristof’s a fellow who likes to save the world. So maybe this is something he can do. Instead of writing about the end of public intellectuals, why not devote a column a month to unsung writers who need to be sung?

Some practical advice for how to be more engaged:

-

Robert Kelchen, What Can We Do?: Work on cultivating a public presence. Academics who are serious about being public intellectuals should work to develop a strong public presence. If your institution supports a professional website under the faculty directory, be sure to do that. Otherwise, use Twitter, Facebook, or blogging to help create connections with other academics and the general public. One word of caution: if you have strong opinions on other topics, consider a personal and a professional account. Try to reach out to journalists. Most journalists are available via social media, and some of them are more than willing to engage with academics doing work of interest to their readers. Providing useful information to journalists and responding to their tweets can result in being their source for articles. Help a Reporter Out (HARO), which sends out regular e-mails about journalists seeking sources on certain topics, is a good resources for academics in some disciplines. I have used HARO to get several interviews in various media outlets regarding financial aid questions.

Oh, look, we’ve built an organization (or two) to connect scholars to the public sphere:

- Amy Fried and Luisa S. Deprez, Talking Points Memo: “…in 2009, when recognizing the gap between those researching possible solutions to pressing policy issues and those in power searching for such answers, Theda Skocpol, a world-renowned professor of government and sociology of Harvard University, led the charge with other top scholars like Jacob S. Hacker of Yale University, Lawrence R. Jacobs of the University of Minnesota, and Suzanne Mettler of Cornell University, to start the Scholars Strategy Network. The organization is a national association of professors and graduate students devoted to sharing their expertise with policymakers and the public to improve public policy and enhance democracy.”

- An Open Letter from the Scholar Strategy Network.

- And finally part of my, unpublished, letter to the editor in response to Kristof: PhD’s are rarely trained to be public intellectuals. Public engagement garners little reward in tenure and promotion structures that favor publication in journals largely out-of-reach to readers not affiliated with a subscribing university library. Last year, with Ford Foundation support, the Graduate Center, CUNY launched JustPublics@365, a project to connect academics with wider publics. More than 400 (with 1,000 more waiting) attended digital media training. More will train at the American Sociological Association meeting in August. Many professors want to engage more fully, they just don’t know how. It’s time for professors to go back to school, and it’s time for universities to reward public scholarship.

Still ruminating on Kristof’s provocation? Did I miss your favorite response? Post a comment.