Academic conferences are being transformed by digital media, and that’s a very good thing.

As a co-organizer of Theorizing the Web 2013 (#TtW13), I was pleased to see this conference happen at the Graduate Center over the weekend. However, being a co-organizer also meant that I didn’t actually get to *see* or hear most of the exciting panels as they were happening because I was preoccupied with hosting duties. The good news is that because of the way academic conferences are changing in the digital era, I could do two things I wouldn’t ordinarily be able to do: have a better sense of what happened in the sessions I missed and have the opportunity to go back and listen to those sessions online when I have time. There are other advantages to academic conferences that are fluidly imbued with digital technologies.

I’ve written elsewhere about changes in the academy being wrought by social media. Specifically, I noted that “Backchannel communications between those attending in-person conferences help academics make connections in real time. Text messaging and Twitter and blog updates allow networks of academics to coordinate in-person connections. Backchannel communications also expand knowledge distribution.” The #TtW13 conference provides an opportunity to illustrate each of these points.

The #TtW13 Twitter Stream: Helping Academics Make Connections in Real Time

The backchannel of conferences in the digital era can be as lively as any of the discussions in session rooms. So, for the panel I moderated on Friday night, I took questions from the audience via Twitter. Here it didn’t really matter whether you were actually in the room or if you were sitting you in your apartment in Paris, you could still ask a question. As it happened, one of the questions I put to the panelists was from a Graduate Center student, Amanda Licastro (@amandalicastro), who was actually in the auditorium:

But it wasn’t necessary to be in the room to follow along at the conference, as Wessel Van Rensburg (@wildebees) notes in this Tweet:

Van Rensburg listened to and live tweeted the David Lyon talk from his home in London:

@Replies + Hugs: Enabling Academics to Have In-Person Connections

It may only be true of the academic conferences I usually attend, but they can be dreadful, unwelcoming places. My impression of academics is that we’re a socially awkward lot that prefers reading books and analyzing numbers over talking to people. One especially status-conscious conference I attend is notorious for the “name-badge-face-scan,” in which attendees routinely scan a person’s name badge, sort for ‘high-status, low-status,’ then smile and say ‘hello’ depending on the status level of the name on the badge. It can be particularly humiliating to walk through the hallways of such a conference having your name badge scanned, and your face ignored because you’re not important enough to warrant a friendly hello.

Digital media, and especially Twitter, have completely transformed my experience of academic conferences because of @replies and in-person hugs. While I’m aware of the kerfuffle happening elsewhere about the “real world” and the “digital dualism” critiques of it, that debate doesn’t diminish the fact that there’s something remarkable about meeting someone in person that you’ve only exchanged messages with via Twitter, as Whitney (@phenatypical) notes here:

The @reply (“at reply”) on Twitter is the primary way that people engage there. It’s public, so it’s possible for other people to see when someone uses the @reply (if they’re following both people in the conversation). The @reply is also a way to have a meaningful conversation with another human being and feel as if you know them. And, you do, in some ways.

The in-person hug is a new feature of academic conferences for me, and it’s tied to those @reply exchanges. That happened when I was sitting next to @sava in one of the sessions. I’ve followed her on Twitter for quite awhile now, and even though we both live in NYC, we’d never met. She’s one of my favorite people on Twitter and I always look forward to her observations about the world. As we were sitting in a session, she peaked over my shoulder as I was updating my Twitter stream, and in a moment of recognition, said “are you Jessie? I’m Sava!” We hugged and there were smiles all around. So much nicer than the cold name-face-badge-scan.

When David Parry (@academicdave) and I met in person for the first time at #TtW11 after following each other on Twitter for years, we agreed there should be some word for that experience. As far as I know, no one’s come up with that word yet.

Livestreams, Recorded Videos, and Sharing Slides: Expanding Knowledge Distribution

The affordances of digital technologies that allow me to catch up on sessions I missed, also enable other people from around the globe who didn’t attend in person to participate in the conference and “feel” as if they were there in person. Here’s what people said about that:

Annamari Martinviita (@amartinviita) from Oulu, Finland joined the discussion. Following her fabulous presentation on MOOCs in higher ed, Bonnie Stewart (@bonstewart) made her slides available for everyone, and posted a note about that on Twitter:

Annamari Martinviita (@amartinviita) from Oulu, Finland joined the discussion. Following her fabulous presentation on MOOCs in higher ed, Bonnie Stewart (@bonstewart) made her slides available for everyone, and posted a note about that on Twitter:

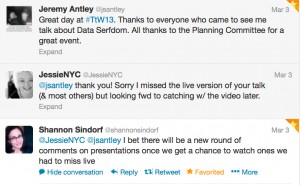

When Jeremy Antley (@jsantley) thanked everyone for coming to his session on “Data Serfdom” – which I saw a lot of conversation about on Twitter – I moaned about not being able to attend, then mentioned the watching the video of it later.

Then, “at replying” to both of us, Shannon Sindorf (@shannonsindorf) astutely predicted a new round of comments on presentations as people got home from the conference and had a chance to watch the videos of talks we missed live.

Then, “at replying” to both of us, Shannon Sindorf (@shannonsindorf) astutely predicted a new round of comments on presentations as people got home from the conference and had a chance to watch the videos of talks we missed live.

This, really, is the point of reimagining scholarly communication, so that we can extend the interesting conversations that we (sometimes) have at conferences beyond the constraints of time and geography.

The big theme of our inaugural JustPublics@365 Summit is ‘reimagining scholarly communication in the 21st century.’ Conferences that use a variety of digital technologies the way #TtW13 did at the Graduate Center this weekend are part of a reimagined academic conference in the digital era. This transformation is, in many ways, a very good thing because it opens up previously closed spaces of academia.