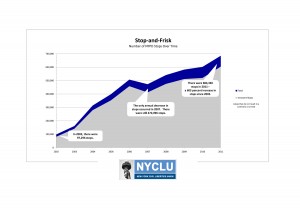

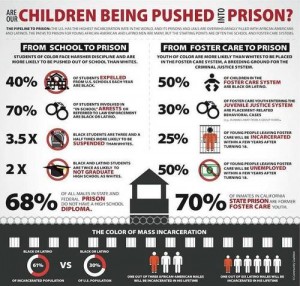

The New York City school police force is the fourth largest police force in the country. It’s bigger than the entire City of Boston police force. This sobering statistic is just one in a huge volume of numbers that tell the story of what is referred to as the “school-to-prison pipeline,” the idea that schools become an early sort mechanism that pushes some children into the hands of the criminal justice system.

(Infographic from here.)

(Infographic from here.)

On Monday, I participated in a round table discussion among academics, activists and journalists as part of the JustPublics@365 Summit on “Resisting Criminalization.” In one of three concurrent round table discussions, participants were invited to discuss ways to people in different arenas (academia, journalism, activism) might work together to “resist criminalization.” All the invited round table sessions addressed three questions: 1) what’s the underlying problem? 2) how do we address it? and 3) what can we do when we leave here to create change?

What follows is a brief summary of the round table discussion on ending the school-to-prison pipeline.

What are the underlying problems causing the school-to-prison pipeline? The broad view of schools as a place where children are channeled into prison was further informed by the stories of social workers, activists, and directors of community-based organizations about what that reality looks like on the ground. On the one hand, students who are still in school don’t have adequate supports. They often need housing, job training, and caring, adult mentorship. On the other hand, the school-to-prison pipeline is the result of particular choices about how society responds to the behavior of young people. Youth need compassionate accountability processes when they mess up, rather than the full force of the correctional system. In addition to holding students accountable for their actions in compassionate ways, participants agreed that we need to hold accountable the multiple layers of systems that produce bad school experiences.

The school-to-prison pipeline also happens because we put police in schools. How do we come to see kids as criminal threats? Well, the police toolkit doesn’t come with very many different ways of viewing a problem. As Aaron Kupchik (University of Delaware) put it: when you put police in schools, more kids go to jail.

(See all the Twitter updates from this session here.)

Many others pointed out that policing (as in police in uniforms) and incarceration are only two of the most visible manifestations of zero-tolerance, criminal-justice-style disciplinary practices that have overtaken schools. Many American schools are put in the impossible position of trying to manage more kids with fewer and fewer resources all the time. This context contributes to an environment where any non-conforming behaviors (including gender presentation or questioning authority) become disciplinary problems.

How do we resist? In addition to the school-to-prison pipeline, many participants talked about the prison-to-school pipeline. We learned about a lot of work being done to help formerly incarcerated people attend University. The experiences of formerly incarcerated people in the room spoke strongly to the value of education as a way out of the criminalization cycle. More than a few participants talked about the need to love and care for young people who have been marginalized. Others agreed and asked what it meant to put love into action in our day to day reality – what does love look like in the context of school? In the context of a community organization? How do we build community power so that parents and students feel confident resisting criminalization at the school and neighborhood level? Can community organizing against these processes be achieved in community organizations as we know them today? Or is the funding model too restrictive?

What can we do? In the last part of the panel we discussed how we could best share the harsh realities of criminalization and all the work being done to resist it with the many “publics” whose minds we need to change in order to be able to mobilize on a larger scale. One activist told a story of distrust and trepidation toward the news media. A journalist who had spent four weeks with him and his organization as they did outreach work with a community of drug users ended up publishing a long news story that focused mainly on the sensational problem of drugs and addicts, rather than the effective work being done to respond to those problems. This raised questions of what community-based organizations can do to be in control of media representations of their work? Or, if that’s not possible, how can both activists and academics make our own media? One journalist spoke of the value of telling specific and detailed stories in order to garner public understanding about issues that can sometimes seem remote. Academics in the room asked activists what kind of information would be useful for their work. Still others insisted on the need to link personal stories to the systemic scale, insisting that both are vital to the process of criminalization. The need for team building and collaboration came up again and again as we listened and made connections between the many vantage points in the room.

You can watch the archived livestream of the session here. Soon, we’ll have a more polished video that we’ll share.