Unless you are blessed with better party invites than I, chances are you know just as little about what goes on in the minds of our toolmakers. All of us, at some point or another, wish that we were BFFs with a coder so that we could finally build our brilliant self-destructing media app that would erase — with the swipe of the screen — all personal messages released into the eternal preserve of digital correspondence. Oh yeah, or RateMyDate.

Kidding aside, regardless of whether digital tools trigger your personal faculties of enthusiasm or ennui, they powerfully shape the way scholars work and the way that work enters both the scholarly and public conversation. And while I have preferred reading little poems composed when poetry was still meant to be sung, I too, have fallen charmed by the potential of tools to shape not just the way we communicate, but the way we think.

And so, in attempt to begin bridging the gap between tool makers and tool users, I begged the kind and illustrious programmer Andrew Badr to answer a few questions via email. Thus far, Andrew has worked on an array of interesting projects, such as the art site Your World of Text which was misattributed to Miranda July and gushed about on Reddit. Currently, he’s working on a start up project called Jotleaf — an interactive web canvas. Though not built specifically with academics in mind, one never knows exactly what prototypes will become tomorrow’s fork and knife. In his answers below, Andrew kindly spills the beans on what it’s like to turn an idea into tool.

1. What is JotLeaf?

A Jotleaf page is an interactive canvas for the web. You can click anywhere on it to starting writing, add pictures, or embed videos or music players. You can style it in different ways, with custom colors and fonts, or invite people to collaborate on a page with you. It’s like a new creative medium. (See jotleaf.com and andrewbadr.com for other descriptions.)

Some ways people are using it:

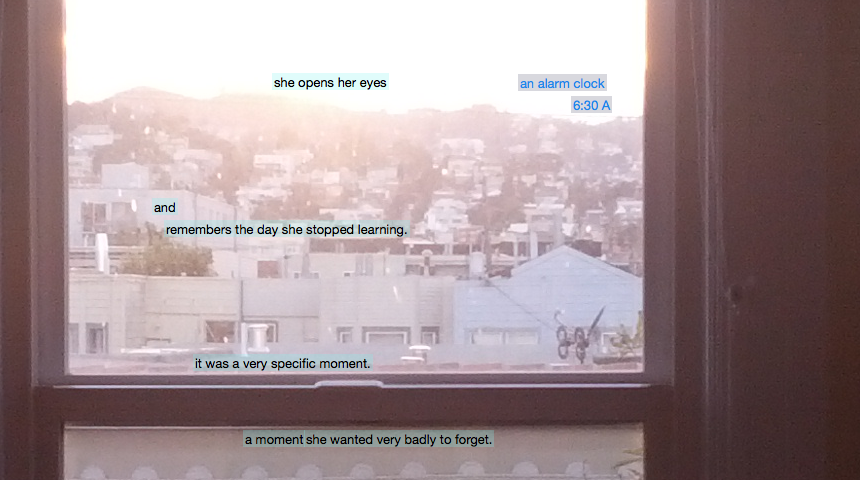

To make art:

-To talk to their friends & fans:

- http://www.tumblr.com/tagged/jotleaf

- Inviting everyone to write on a birthday card for someone

- As a personal notepad for ideas

To some degree, we are trying to let the community guide our understanding of what this new medium is best suited for. But we also think things are possible that it isn’t being used for much yet, like creating more general-purpose websites, which guides some of the feature development.

The idea for it came out of a previous site I did, called Your World of Text. See http://yourworldoftext.com/home/ and the description on my homepage (under “Some Things I’ve Done”). Your World of Text is an art project, and I want to keep it that way. But for the past couple years, I’ve been thinking about what it would mean to turn the same kind of interactivity into a “startup”. Jotleaf is the answer to that question. And that’s just as much about my attitude towards the project, and how the site is presented and marketing, as it is about features.

I first saw Jotleaf in my mind some time in April of last year (2012). I started working on it part-time for a few months, then more seriously starting in September. In December, a friend from college joined the project, and we committed ourselves to it full-time. He lives in Italy, so in January I moved out here for three months to work more closely with him. We got some funding from friends and family — enough for a few months, to try to get the site to the next level and then raise a real round. In May, he’s moving to San Francisco for three months, and we’ll continue our work there.

2. What does building such a tool entail?

A day’s work, at this point, is mostly writing code. Code to make the site do new things; make it look better; make it more reliable; and fix any problems that come up. There’s also marketing and customer support: Facebook and Twitter accounts, a monthly newsletter, and constantly talking to our users to see what they like and don’t like about the site.One challenge is that people can’t really tell you what they want. The best thing for your startup might be to radically change the product, but a user will never say that. Or say your site is slow — that will drive people away, but people don’t necessarily consciously realize that. So that’s where measurement and intuition come in.

3. How did you personally get involved in this line of work? Have you worked on any other similar projects?

I’ve been making websites since high school, and experimenting with the medium from the start. I didn’t know it was “what I wanted to do” until late in college though. The big appeal to me is how you can put something out there, and then the next day — you make the right thing — the whole world could see it. You aren’t limited by who you know, or your credentials, or your hourly wage. It’s an exponential game.

4. Tell us about what’s most exciting in digital innovation today!

For the most exciting things today, Chris Dixon pretty much lists them out in this blog post.

But programming is always exciting, because it builds upon itself in a way that no other human endeavor has done. Something that took a year to program ten years ago is now a page of code that you could write in a day. And it’s been happening like that for decades, building layers of abstraction on top of each other, and it’s going to keep happening. The amount of leverage that one person has is amazing, and is going to keep getting more so.

5. How might academics better collaborate with digital folk to improve upon or create new tools?

Re: academia, to be honest it’s hard to imagine new tools coming fromthat direction. The best people to create the tools are the people who use them. Academics should create tools insofar as they are practitioners. The most useful stuff I see out of academia is studies about user behavior.

6. You’re in Turin right now. Anything interesting to report about the international digital scene, or how exactly you started collaborating with an international partner?

I don’t know nothing about no international digital scene. I’m in Turin because my friend from college lives here. I don’t really hang out with anyone besides him, his wife, and their two year old daughter. 🙂

7. And perhaps not-relevant, but have to ask: Are you socially-engaged with any academics in a way that influences the way you think about the potential of technology?

The only way I can think of that I’m socially involved with academics is that I follow @golan on Twitter and he posts interesting stuff sometimes.

8. What inspires you?

What inspires me? Well, if you mean what’s my source of ideas, I’m just thinking about the web all the time. I have at least one idea. I’ve literally dreamt several website ideas. If you mean motivation… I want to push the web forward, and change people’s conception of what it could be, and create a space for new kinds of creativity and communication, and make something big.

9. If time and money weren’t an issue, what would you build?

If money weren’t an issue, I’d hire my friend Brian. If time stopped, I’d first write a framework in which to write a framework in which to write my website. But basically I’m doing what I want to be doing right now.

Photo Credit: Joe Aranda, from JotLeaf.com.