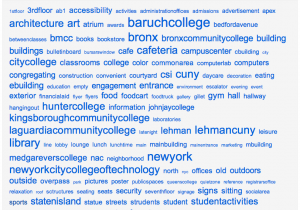

Young people entering college today have grown up immersed in a multimedia digital environment. Yet, the classroom environment they encounter often reflects nineteenth-century pedagogy of “walk and chalk,” of a lone professor standing in front of a chalk board, professing about their subject. Not surprisingly, emerging research indicates that teens are not engaged by this antiquated mode of instruction. Moreover, the work force our students are entering demand a different kind engaged learner.

(Image Source)

At CUNY, I’m also honored to have a wonderfully diverse student body. That incredible diversity presents some pedagogical challenges. How do you have a conversation, use examples, illustrate points when people don’t share a common cultural background? Once in a gender course, I tried to use an exercise about the gendering of Halloween costumes only to have it fall flat when half my class reminded me that they didn’t grow up with Halloween and the whole thing still seemed bizarre to them. In another course, the students included one woman who had been a sargeant in the Bosnian army and another who had fled the famine in Somalia.

This set of challenges required more of me as instructor than writing a new lecture or getting students to put their chairs in a circle. We needed to find a way to have a meaningful, deep discussion about the course material. And, unfortunately, the books and assigned readings were often as much a barrier as they were a gateway to those discussions.

In re-thinking my strategy in the classroom, several years ago I began experimenting with various forms of digital media to engage students in learning the abstract, sometimes difficult, concepts of the basic sociology curriculum. My explorations led me to documentaries, a medium experiencing its own digital revolution, as a mechanism for engaging students, encouraging critical thinking, and enticing them to complete assigned readings.

(Image source)

For at least a decade, educational scholars have urged teaching critical media literacy through popular culture. Popular culture is often an easy pathway to student engagement because it has already captured young peoples’ attention, and then instructors can scaffold more difficult concepts around that interest. The images that drive much of popular culture may be part of the key to this as a pedagogical strategy. Scholars in cognitive psychology are finding that students learn more deeply from visual media (words and pictures) than from words alone (Mayer 2001).

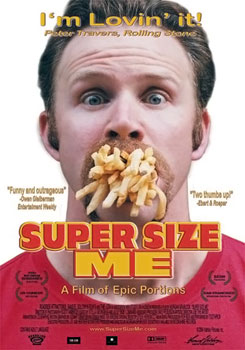

Shifting Paradigms: Docs, Digital Media & Distribution

Today, there are simply more documentary films in existence than ever before due to the rise in the independent and documentary film industry, widespread use of digital video cameras by the general public, and the rise of documentary-style television. Prominent documentarians such as Michael Moore (e.g., Sicko, 2007; Fahrenheit 9/11, 2005), Davis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth, 2006), and Morgan Spurlock (e.g., Super Size Me, 2004) have experienced mainstream commercial success with the theatrical release of their films. In addition, documentary-style television shows (e.g., Discovery Channel and A&E have re-branded their entire programming schedules around these shows) and made-for-television documentary series (e.g., Transgeneration for Sundance Channel) abound on cable channels. HBO Documentaries led by Sheila Nevins, an arm of the cable powerhouse HBO, has built an impressive archive of documentary entertainment over twenty years, many of those titles concerned with social issues. For instance, in a landmark collaboration between National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, HBO launched Addiction(2007), an award-winning collection of documentary films by some of the leading directors in the field. The ascendancy of the documentary form has led some commentators to suggest that we are experiencing a “golden age” of documentaries.

(Image Source)

At the same time that professionally produced documentary television and films are rising in prominence, the price of digital video cameras and digital editing software are falling, effectively lowering the barrier to would-be documentarians. The shift from more expensive analog celluloid film stock to less expensive digital video, and the equally important shift to digital editing software, has meant that more people are producing, directing and creating documentaries. Indeed, digital video technologies are becoming commonplace in American households.

The do-it-yourself digital video technology allows almost anyone to document the most microscopic details of their existence and make them available to the larger public, in effect becoming a new, visual form of memoir. This democratization of documentaries further contributes to their wide availability for the sociology classroom and increases the likelihood that beginning students will have some familiarity with the documentary form. Taken together, the rise in the number and the success of professionally-produced documentaries alongside the DIY (do-it-yourself) documentary and digital video means that today there is an ever increasing array of documentaries from which instructors may choose. Given this greater selection, it is now likely that there is a documentary film that addresses nearly every topic covered in the typical introductory sociology class. Not only is it likely that there is a documentary for each unit in an introductory college class, it is also now possible to acquire said documentaries through a shift in distribution networks.

Distribution networks for films shape the way they are used in the college classroom. Professors have long used feature films as teaching tools in college courses. At least in part, this pedagogical practice was shaped by the distribution networks for feature films produced by Hollywood studios. Conventional distribution networks, such as chain video stores and cable television channels, made feature films widely available to the general public and thus more accessible for sociologists interested in using films in the classroom.

The explosive growth in the production of documentary films means that there are simply more documentaries to distribute. And, the commercial success of a few of those documentaries released in theaters has made distributors more aware of the broad audience for the non-fiction film. Most importantly, vastly diversified distribution networks mean that many of the economics of the “long tail” work to the advantage of documentaries without a wide theatrical release.

(Image Source)

According to Chris Anderson’s theory of the long tail, creative products and content of all kinds with a smaller than mass-market appeal can find modest commercial success through distributed networks; so, for example, one can now find obscure tunes via iTunes which would have once been difficult to locate in record stores based on old distribution networks that relied on mass-market appeal.

And, this shift in distribution networks has affected documentaries as well, most notably through the online retailer Netflix which has gained a reputation for distributing relatively hard-to-find documentaries. In addition, literally millions of short documentary films and clips from longer documentaries are available at no cost through online video portals, such as Hulu.com, PBS.org, and YouTube.com.

Taken together, these shifting trends in digital video technology and distribution networks have led to an increase in the number of non-fiction films being produced, and this increase in the number of films has driven down the overall cost of acquiring documentaries for individual instructors and educational institutions.

Transforming (my) College Classroom through Documentaries

The wider accessibility of documentaries has transformed the way I approach the classroom. Now, I combine documentary films with peer-reviewed articles or other assigned readings around key concepts. My background and training is in sociology and I teach in a public health program, so the content I teach is, broadly, in the area of “medical sociology.”

In courses I design, there is some overlap between the films and the readings, this repetition is meant to reinforce the material for students, as well as provide opportunities for insights about the connection between the films and the readings. In order to highlight the importance of authorship and credibility, near the beginning of the semester I describe for students the process of peer-review for publication and contrast this with the publication process for print-based journalists and for new media journalists, such as bloggers.

In lecture and class discussion, I drive home the importance of peer-reviewed literature and emphasize that this is the research that professionals consult and rely upon for their work. I challenge students to master the ability to find and read the peer-reviewed literature as a basic standard for becoming a college-educated and engaged citizen. As I introduce the first documentary to the class, I revisit the issues of authorship and credibility in visual texts. For each film, I provide students with a “Video Worksheet” prior to the class the day the film is shown through the a learning management system (e.g., Canvas, Moodle, Blackboard). Students are required to bring the worksheet with them and to complete the assigned reading before the class. The “Video Worksheet” includes questions about the key concepts, the content of the film, the connections between the film and the assigned reading, and asks about the mechanisms the filmmaker employs to convey their message.

After the film, class discussion – either in small groups or with the class as a whole – focuses on answering the questions on the worksheet. I collect these worksheets and give participation points based on completion, but do not grade them closely for accuracy; rather I rely on the class discussion following the films to drive home the correct answers. Questions from the worksheets are often adapted as exam and quiz questions. The “Video Worksheets” also help scaffold the development of students’ critical media literacy skills by helping them understand the “point of view” (POV) of the director by analyzing the component parts that make up the documentary.

Can you give me an example?

As just one example of this approach, I offer this example of one of the more difficult topics I cover: medical sociology and race.

Race, a socially constructed category, is nevertheless an important determinant of health. This can be a difficult concept for students to understand. By providing some historical context for contemporary health disparities, a deeper understanding of racial discrimination in the U.S., as well as the ethical violations in medical experimentation can be an effective strategy for teaching this concept. To address this topic, I show “The Deadly Deception” (Denisce Di Ianni, writer, producer and director; Films for the Humanities & Sciences, 1993, 60 minutes), a documentary that deals with the Tuskegee Syphilis Study conducted by public health officials in the U.S. from 1932 to 1972. The film features first-person accounts of African American men who were enrolled in the study and a number of doctors who were investigators on the study – some of whom objected to the study and one white doctor who still defends the study as a worthwhile scientific endeavor. In addition, the film features archival footage and interviews with experts in medical sociology. The documentary is quite affecting and holds up well even though it is now older than most of the students.

For most traditional-aged college students (born around 1995 or 1996) who are unfamiliar with the history of the Tuskegee study, the film is compelling. For an introductory class, the power of this documentary is further enhanced through the assigned readings and there are a number of articles that work well with this film. For an early undergraduate course, “The Tuskegee Legacy: AIDS and the Black Community,” (1992) is a short (three page) article written in easily accessible language. For more advanced classes (and learners), Thomas and Crouse Quinn’s article, “The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: Implications for HIV Education and AIDS Risk Education Programs in the Black Community,” (1991) works well as a companion reading to the documentary. Both articles provide a connection between the historical background on the Tuskegee study and contemporary distrust of medical intervention on the part of African Americans. Rather than seeing resistance to medical professionals as an artifact of social isolation, lack of education, or cultural superstition, these readings provide students a way of seeing the deeply rooted, systemic racial oppression that pervades the U.S. and the consequences this has for the lives of African Americans. The film students with an engaging and critical background to the history of racial discrimination in the U.S. and its attendant health consequences. The film also raises important questions about the ethics of medical experimentation and about public health research that focuses exclusively on one racial or ethnic group. The peer-reviewed readings take the background provided by the documentary film as a given, and add further complexity by exploring the implications of this history for the health of contemporary African Americans. Without the film, most students unfamiliar with the history of the Tuskegee experiments would have a more difficult time with the peer-reviewed readings; without the peer-reviewed literature, students who only saw the film might erroneously assume that the lessons of Tuskegee were confined to a remote historical period. The “Video Worksheet” and class discussion build on theses lessons and introduce students to critical media literacy concepts by asking questions about the point-of-view of the filmmakers and the way they used particular filmic techniques to construct an argument visually.

But, is this an effective strategy for teaching and learning?

I’ve published a couple of pieces on the results of some research I did on how this teaching method works. The shortest answer is: it seems to work well for increasing student engagement in course material. I have a good deal of data (both quantitative and qualitative) on student responses to this method, but perhaps my favorite is this quote from an undergraduate student:

“The videos helped because they were usually taking a stance on an issue, while the text briefly described the arguments/positions. Seeing and hearing video is much better than reading the text because the historical footage, impassioned speeches, and other interviews are relayed with much more clarity. The videos are easier to watch for 90 minutes than 90 minutes of reading the text, so even if the information was the same, I grasped more of it.”

As an instructor, hearing a student say this method of teaching enabled me to “grasp more of it” is gratifying.

I measure the effectiveness of this as a teaching strategy in other ways, as well, such as the number of other instructors who have adopted this method. The wiki I set up to catalog documentaries has, at latest count, received more than 67,000 visitors.

We are living in a different era, one that is saturated by multimedia and students come into the classroom expecting to learn this way, but they are often disappointed. This method of combining visual culture through non-fiction films digitally distributed with traditional peer-review literature as a way of teaching critical thinking provides a way forward.

If you’d like some help getting started using this teaching method, here are some resources:

Happy doc watching! 😉