Wendy Hsu, Scholar of Sound

I started a blog when I began my dissertation research in 2007. YellowBuzz was meant to share my field notes from observing and participating in the indie rock music scenes first with my research associates and by extension the broader public online. These public field notes were written in the style of performance and album reviews accessible for a general audience outside of academic ethnomusicology. I took the voice of a field correspondent and committed to a fast no-more-than-a-couple-of-week turnaround. Through highlighting these unusual performances and connecting them to theories of identity formation and community building, my blog lived in a liminal space in which it served both as a part of the process and a product of my research. My participation as a blogger in these music scenes gave Internet-visibility to the Asian American musicians that I came to know in my fieldwork. At a high point, my blog became a hub for readers interested in all things related to Asian and Asian American indie music scenes, and was subsequently cited in two Wikipedia articles. My blog and related presence on Twitter (@wendyfhsu) generated a social and discursive space that takes seriously these minority musicians’ below-the-radar cultural production within the public domain. The observations I made as a blogger led me to explore a series of inquiries related to musicians’ digital sociality and theorize the formation of digital media diasporas in the context of post-9/11 racial and geopolitics.

Blogging and academic writing are two modes of knowledge production. They are framed differently – short vs. long, informal vs. formal, impermanent vs. permanent – and for these reasons, they yield different rhetorical consequences. Their audiences might overlap, but for the most part don’t. In my own work, I find and leverage the productive tension between these two modes of communication, where one ends drives the beginning of the other. The continuum between blogging and research writing generates a set of reflexive dynamics that can deconstruct the notion of the “field” (Kisliuk 1997). Sharing bits of field findings live as the research is undergoing can question the subject-object binary in ethnographic research. Tricia Wang suggests that live fieldnoting makes visible meaning-making, a process that’s critical to ethnographic work, but is often not made transparent until the publication of a monograph or a peer-reviewed journal article (2012). The multi-year arc of a print-based scholarly publication project for academic ethnographies present a dissonance with the principle of participatory engagement. Conducive to fast and creative reuse of content, digital and online media can contribute to changing modes of scholarly communication. Elements such as media synchronicity; networked, iterative structure; and efficiency make digital media a great vehicle to open access to scholarly materials. These digital affordances can drive the transformation toward an ethos of openness. For those of us engaged in ethnographic work, this means a wider and more open ethnographic feedback circle – from fieldwork to publication and impact in and around the field.

In the space below, I offer two stories about how I conceptualize openness in my own scholarly communication practices, with a bit of commentary on the politics and economics around scholarly transparency from the perspective of a young non-tenure-track scholar. I also hope that these stories serve to illustrate the possibility of a generative relationship between blogging and journal article publication.

Seven years later after I started Yellowbuzz, I’m still blogging about my research. I have experienced a few arcs from the time of field research to peer-reviewed journal article publications through my research project lifecycles. A blog post I wrote in 2007 marks the beginning of my field engagement with the band Hsu-nami. I presented a paper about the religious imagery in the band’s music at SEM in 2008 and developed this paper into a full chapter in my dissertation which was completed in 2011. An article-length version of this chapter became published in a peer-reviewed journal in 2013, seven years after my initial research interaction with the band. My second peer-reviewed journal article publication followed a similar arc.

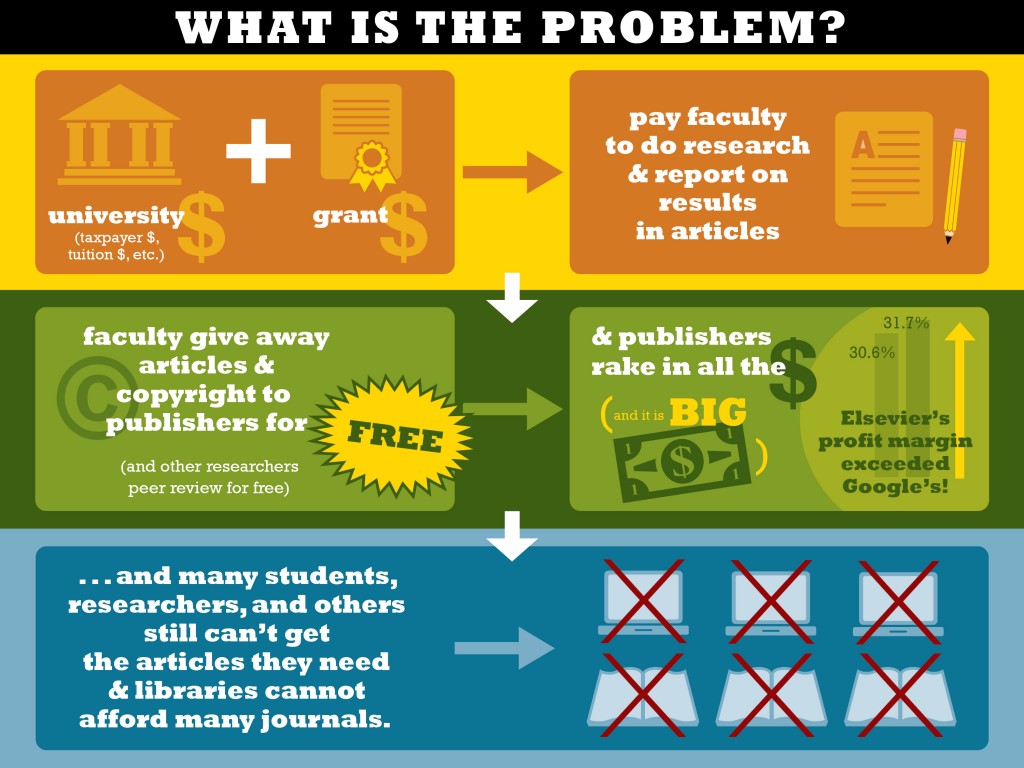

Both of these publication arcs concluded with a less than ideal closeness. My research associates, among them professional journalists, tried and failed to access the article about their music. What does this say about the informational and epistemological politics? Both journals that I published in are non-open-access with fairly strict copyright terms. As a young scholar, I don’t have the luxury of time to negotiate to retain my rights as an author. In the case of Asian Journal of Communication, a journal under the Taylor and Francis Group, I was given the “option” of paying $2950 to make my article open access. This option appeared to be a non-option for me, a postdoc fellow in a double-contingency trap: her contingent job situation as a non-renewable researcher in a higher education institution; the contingency of her job prospect on her publishing successes. To me, an “open access” option that requires an exorbitant amount of money in order to administer what is proclaimed to be an open, unrestrictive process itself is a contradiction. Like other neoliberal models, this framework equates the labor and production of academic knowledge with its consumption, and outsources the financial responsibility to deliver products to the content producer. Taylor and Francis’s ostensibly open access option capitalizes on openness, a value that is increasingly important to the scholarly community. In more than one way, it defies the tenants of the actual open access movement. So I tweeted my stance resoundingly:

A more open and efficient research publication arc I experienced was with my project on digital ethnography. Throughout this project lifecycle, I experimented on various digital platforms to play with the content and form of my research expressions. In these experimentations, I iterated my research in an open form as a post on a blog associated with my graduate fellowship program at University of Virginia; then as I developed my work within a postdoctoral context, I began publishing it on my personal site. Two years ago, an editor-at-large of DH Nowand by extension Journal of Digital Humanities spotted my work on blog and contacted me to explore an interest in developing the blog post (on my personal site) into a full-length journal article. Around the same time, the editor of theEthnography Matters blog invited me to serialize my research on digital ethnography. I thought I would take this set of opportunities to develop my blog post series, staging it as an open forum to invite feedback on my work. This helped me polish the writing for the eventual manuscript submission for theJournal of Digital Humanities. More than just an open access journal, DH transforms the peer-review process by leveraging the open web protocols to source and distribute scholarly content. The editorial and review process begins with an identification of a likely submission based on blog feedback, comments and social media metrics. Then the journal provides “three additional layers of evaluation, review, and editing to the pieces.”

Writing within a network of peers and colleagues makes the process of ideation deeper, more productive than writing in isolation. The evaluation and review process with JDH, for the reasons above, felt so human to me. Each touchpoint was encouraging and yielded constructive insights to further the development and refinement of the paper. When the paper was published in this past spring, I felt confident about the timeliness and relevance of my work. Through its lifecycle, this research project published content in various lengths, types, and formats. This multiplicity of form and content reached a wide network of readers, ranging from academic to applied ethnographers, digital humanities scholars, and geographers.

The technological affordances of these publication platforms allowed me to engage with complex layers of content and voices across disciplinary and social perspectives. Kim Fortun and Mike Fortun compares the scholarly community to a village, a “community of practice [that] cannot prosper if all it encounters is judged with established concepts of what is proper and valuable; the village should not be taken out of history. Instead, we must deliberate and figure out how to respond to changes in the landscape, new problems, new technologies, and new connectivities” (2012).

Publishing, to me, in its simplistic sense, is to make something public. If our public precludes those who have been our research associates, or individuals without institutional affiliations or access to scholarly journals, then we should rethink how we communicate our scholarship. Lastly, I return to the question of research impact, an inquiry central to the ethnographic perspective and a critical step of the ethnographic feedback loop. The issue of transparency can set the course of impact of our research. Having an open and transparent channel of communication is the beginning of a meaningful dialogue we ethnomusicologists can foster with the public. Informational openness, however, is a complex discourse that requires further contextualization and its discussion would not complete without a full consideration of access, ethics, and responsibility (Christen 2012). We’re living in a moment where the value of scarcity associated with industrial mode of production (Suoranta and Vadén 2008:131) is being challenged by the dispersed openness afforded by digital media. The scholarly publishing industry itself is a cultural field with policies and infrastructures driven by commercial values (Miller 2012) that mostly defy public interests. We should maintain our critical viewpoints as we engage with our own scholarly communication practices.

* * *

Works Cited

Christen, Kim. 2012. “Does Information Really Want to be Free? Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Commuincation 6:2870-2893.

Fortun, Kim and Mike Fortun. 2012. “Separate But Entangled: Peer Reviewed But Not Conservative,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (1): 385-411.

Kisliuk, Michelle. 1997. “Un(doing) Fieldwork: Sharing Songs, Sharing Lives.”Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Colley. New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller, Daniel. 2012. “Open Access, Scholarship, and Digital Anthropology.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2(1):385-411.

Suoranta, Juha and Tere Vadén. 2008. Wikiworld: Political Economy of Digital Literacy, and the Promise of Participatory Media. Paulo Freire Research Center, Finland (http://paulofreirefinland.org) and Open Source Research Group, (http://www.uta.fi/hyper/projektit/opensource/), Hypermedialab, University of Tampere, Finland.

Wang, Tricia. 2012. “Writing Live Fieldnotes: Towards a More Open Ethnography,” Ethnography Matters, [retrieved from http://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2012/08/02/writing-live-fieldnotes-towards-a-more-open-ethnography/] (accessed on September 27, 2014).

~ This post was written by guest blogger Wendy Hsu and was originally published at The Ethnomusicology Review (October 21, 2014).

Wendy Hsu is an ethnographer, musician, and community arts organizer who engages with multimodal research and performance practices informed by music from continental to diasporic Asia. She has published on Taqwacore, Asian American indie rock, Yoko Ono, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Bollywood, and digital ethnography. Her postdoctoral work engages with Nakashi (那卡西) street music-culture in postcolonial Taiwan and practices of music and mobility of Taipei’s urban underclass. Hsu received her PhD in the Critical and Comparative Studies in Music program at the University of Virginia. As an ACLS Public Fellow, Hsu currently works with the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs. She recently completed Mellon Digital Scholarship Postdoctoral Fellowship in the Center of Digital Learning + Research at Occidental College where she researched and taught ethnographic methodology, digital pedagogy, digital sound studies, and community-based participatory research. An active performer, Hsu is a founding member of ethnographic ghost pop band Bitter Party, vintage Asian rock band Dzian!, improvised music trio Pinko Communoids, and Yoko-Ono-inspired noise duo Grapefruit Experiment. She also co-founded engaged innovations collective Movable Parts and experimental music group HzCollective.

Typically, content analysis is a linear, step-wise projection from data collection to analysis to interpretation, while an ethnographic approach is reflexive and circular. Aiming to meet in the middle, ECA is “systematic and analytic, but not rigid”

Typically, content analysis is a linear, step-wise projection from data collection to analysis to interpretation, while an ethnographic approach is reflexive and circular. Aiming to meet in the middle, ECA is “systematic and analytic, but not rigid”