As we come to the end of the meta-MOOC #FutureEd conversations prompted by Cathy Davidson and our lunchtime interlocutors here at CUNY, I’m pondering how we measure the impact of such a course, and more broadly, the impact of the work we do as academics.

In a recent post at The Chronicle of Higher Ed, Douglas Howard considers the unfinished feeling of so much teaching in general:

Did Jim, who talked about becoming a therapist, go on to graduate school in psychology? Did Jessica, who argued so passionately in class against the death penalty, make it as a lawyer? We fill in the blanks about them based upon what we know (or think we know), and tell ourselves that their stories ended the way that we hoped.

Teaching, in this regard, is the great open-ended narrative, the romantic fragment, the perpetually unfinished symphony.

The fact is, we almost never know if a course we taught, or a book we wrote, or an article we labored over, has any impact on anyone else.

Mark McGuire has a thoughtful post at HASTAC about the difficulty in rating transformational experiences specifically in the context of a MOOC, such as the one on #FutureEd:

We rate hotels, music, live performances, movies, etc., so that others are able to make an informed decision about how to best invest their time and money. Rating and reviewing MOOCs seems like a sensible thing to do for similar reasons, and it would not be surprising to see such a practice develop. However, unlike a hotel or restaurant franchise, a living, changing, organic learning experience cannot be packaged, replicated, and sold to consumers who are looking for a satisfying (and predictable) product or service. It can’t offer the same experience to the same person twice, and one person’s experience may not be a good indicator of the experience another person will have. A transformational learning experience is like a good pot luck dinner party — you might have had the time of your life, but it can never be repeated.

I like the dinner party metaphor for teaching much better than the “unfinished symphony,” perhaps because I’m much more likely to attempt a dinner party than a symphony. I do think that there is a kind of alchemy in teaching, and good dinner parties, that makes it easy to assemble the same people, elements and conditions but difficult to replicate magic when it happens.

It’s also difficult to think about how one might measure any of this. Unfortunately, to my way of thinking, the word “measure” has become synonymous with “quantify.” When we think of measurement exclusively in terms of quantification and counting, we lose a great deal of the story of impact.

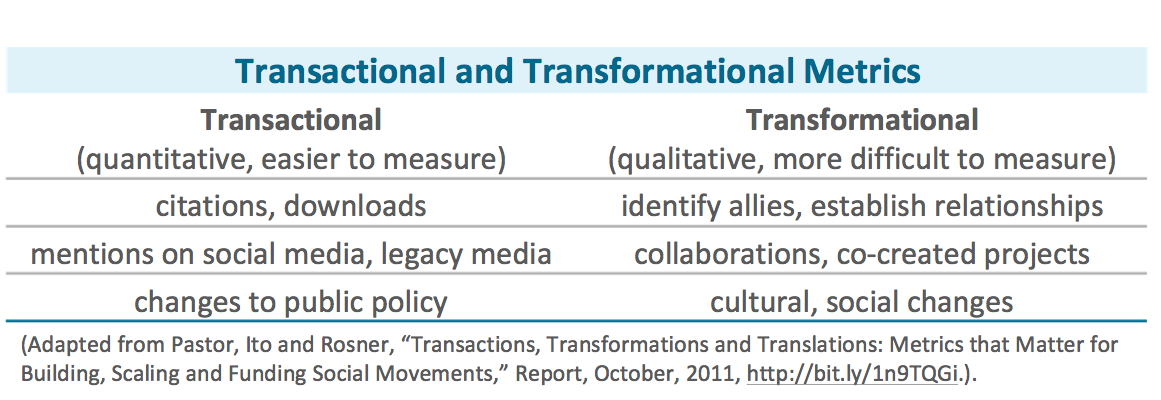

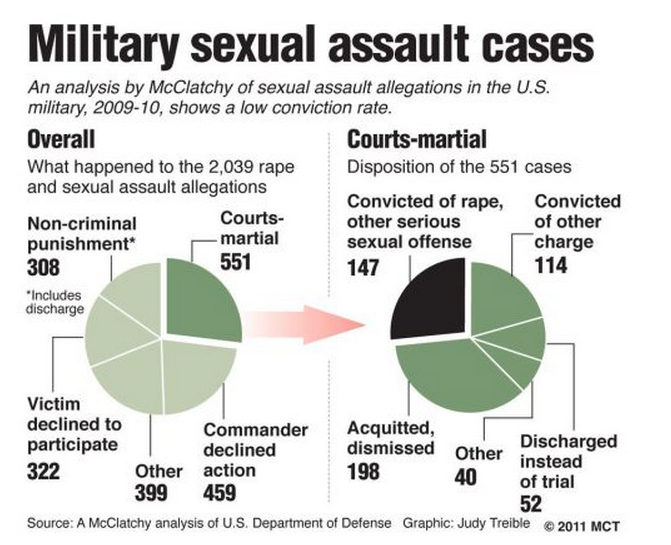

I want to suggest an alternative way of thinking about impact that includes qualitative measures. In the chart below, you’ll see a way of conceptualizing “transactional” measures – quantifiable things we can count, alongside “transformational” measure – qualitative measures, that are more difficult to count but represent more lasting change.

(Chart content from Bolder Advocacy, h/t gabriel sayegh.

Chart design by Emily Sherwood)

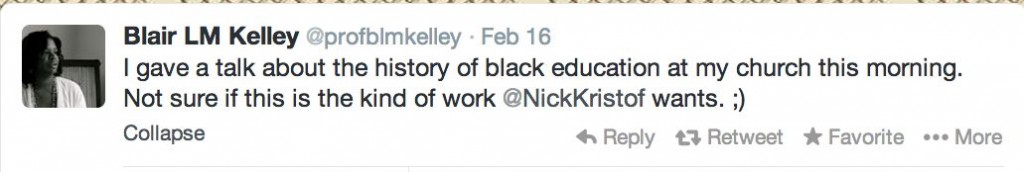

In this schema, transactional metrics include both traditional (or “legacy”) academic measures of impact such as citations, along with alternative measures (or “altmetrics”), such downloads, or mentions on social media. Quantitative, transactional measures of impact can also include lasting social change, such as changes to public policy. One of the things I like about this conceptualization is that it illustrates the incremental change that altmetrics represent. In other words, altmetrics are just another way of counting things – downloads and social media mentions, rather than citations – but it’s still just counting things. Counting and quantification can tell us somethings, but it doesn’t tell the whole story.

On the “transformational” side are those things that it’s difficult, perhaps even impossible to measure, but that are so crucial to doing work that has a lasting impact. These include identifying allies, building relationships, establishing collaborations, and co-creating projects. Ultimately, transformational work is about changing lives, changing the broader cultural narrative, and changing society in ways that make it more just and democratic for all. These kinds of transformations demand a different kind of metric, one that relies primarily storytelling.

How might this work in academia? Well, to some extent, it already does.

To take the example of teaching, you may have gotten the advice – as I did – “save everything” for your tenure file. This advice often goes something like, “everytime a student sends you a thank you card, or writes you an email, or says, ‘this class made all the difference for me’ save that for your tenure file.” That’s part of how we ‘finish the symphony,’ to borrow Doug Howard’s metaphor, we get notes from students, we compile those into a narrative about our teaching. It’s impartial, to be sure, but it’s something. The comments that students add to teaching evaluations are another place we see that impact in narrative form, although these are so skewed by the context of actually sitting in the class that it misses the longer term impact of how that course may have changed someone.

For the diminishing few of us on the other side of the tenure-hurdle, think about those letters of recommendation we write for junior scholars. Whether we’re writing for someone to get hired, promoted, or granted tenure, what we’re doing when we craft those letters is creating a narrative about the candidate’s impact on their corner of the academic world so far. Of course, we augment that with quantitative data, “this many articles over this span of time,” and “these numbers in teaching evaluations.”

The fact is, we already combine transactional and transformational metrics in academia in the way that we do peer evaluations. What we need to consider in academia is expanding how we think about ‘impact’ and realize the way that we already use both quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate and assess the impact of our work.

More than this, we need to reclaim storytelling and narrative, augmented by the affordances of digital media, to tell stories of impact that make a difference.