There are far-reaching changes happening in higher education today, and I think we need some new – or a least, borrowed – terms for talking about these changes.

Journalists and scholars of journalism talk of “legacy” news organizations — such as The Philadelphia Inquirer (now defunct). The Philadelphia Inquirer, like other legacy news organizations, was based on print publication and relied on newsstand purchase or home delivery option for economic viability. Ultimately, it wasn’t able to make that succeed as a business model (see C.W. Anderson’s excellent Rebuilding the News. Anderson, @chanders on Twitter, is a CUNY colleague).

In contrast, there are many news organizations that are increasingly “digital” in the way they both gather and report the news, and the way they make money. Most notably, The New York Times now includes remarkable digital content, such as Op-Docs and Snowfall; and, it relies on a digital subscription model in addition to print sales. To be sure, there are lots of differences between academia and the news business, and I want to be clear that I’m not suggesting an easy parallelism between the two. I do, however, think that this language may be useful for framing how we think about some of the changes in higher ed.

(Flickr Creative Commons)

(Flickr Creative Commons)

LEGACY ACADEMIC SCHOLARSHIP. What I’m calling a “legacy” model of academic scholarship has distinct characteristics. In broad terms, “legacy” academic scholarship is pre-21st century, analog, closed, removed from the public sphere, and monastic. I think that this is mostly going away, but only partially and in piecemeal fashion. What did the legacy model of academia look like?

(Wikimedia Commons)

(Wikimedia Commons)

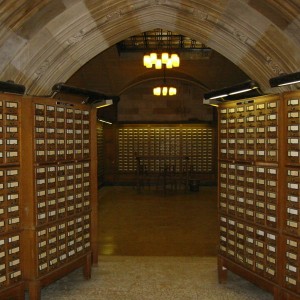

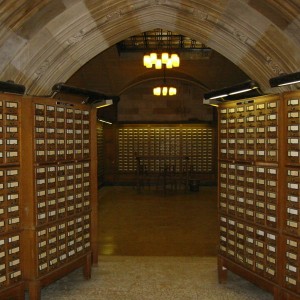

Within a legacy model of academia, the only option for publishing was in bound volumes or journals. We typed words and paragraphs on paper. We had to use white out to make corrections on things we typed. In order to “cut and paste,” we would literally cut sections of paper, a paragraph at a time, and then paste them with glue or tape in different order. We would go to libraries to find and read information. We would use card catalogs (like the ones pictured above) to look things up.

In order to measure or demonstrate the impact of our research (at least in sociology), we used something called the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), which tracks the number of times a particular work by an individual author has been cited by others in the peer-reviewed literature. So, for example, if I published an article then the SSCI would list my name and then underneath my name track all the citations referencing that article. In effect, the SSCI is a method for counting citations as a measure of academic success. The more citations in the SSCI one has, the bigger success as an academic. In many sociology departments, it was common practice to rely heavily, if not exclusively, on the SSCI to assess a scholar’s prominence in the field. Tenure and review committees would actually use rulers to measure the number of inches beneath a scholar’s name within the SSCI as a way to assess impact. This crude metric of counting the number, and number of inches, of citations is characteristic of 20th century legacy academic scholarship.

(Flickr CreativeCommons)

(Flickr CreativeCommons)

DIGITAL ACADEMIC SCHOLARSHIP

To be sure, academic scholarship is being transformed in the digital era. In contrast to the 20th c. legacy model, the emerging, 21st c. model of academic scholarship is digital, open, connected to the public sphere, worldly.

To state the obvious, there has been an expansion of digital technologies. For some, this has been transformative because it is so different than the analog way of doing things. For others who were born after the digital turn, these ways of doing are simply the way things are. Whichever group you fall into, these digital technologies have already begun transforming scholarly communication.

Simply put, the shift from analog to digital is about code, coding information into binary code of 1’s and 0’s. When this happens, it fundamentally changes how we can manipulate data. That is, information (or ‘data’) is easier to move around, edit, analyze in digital form then it is in analog. Think for a moment about the difference between “cut and paste” when it involves paper scissors clue and tape versus the simple keystrokes of control-x and control–v. This illustrates a key difference between analog and digital.

The shift from analog to digital and the explosion of different sorts of technologies are already affecting how we do our jobs as academics. Rather than comb through a card catalog, we look things up on Google Scholar. The whole notion of a “library” is now one that’s digital, distributed, like the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), which is a real game-changer when it comes to libraries in the digital era. While physical libraries remain crucial, the expectation among academics for how we use libraries has changed.

As scholars we increasingly expect, and even demand, that there are digital tools within those libraries that we can use from any location, at any time. In fact, most graduate students and faculty I know would be outraged if they could not access their library at any time from any place. In many ways, libraries have led the digital turn in higher education and it is where academics have most embraced the digital.

Digital technologies have changed how we keep track of things we have read, citations, and bibliographies. With tools like Zotero, we can create bibliographies, keep track of citations, and share them with others who have similar interests.

Digital technologies have changed how we write. Technologies such as Commentpress (a WordPress plugin) make it possible to write collaboratively and make peer-review an open, transparent process. Several people in the digital humanities have used this technology to compile entire books for well-regarded academic presses. One of these is my colleague, Matt Gold, who issued a call for papers for his Debates in the Digital Humanities, and in 14 days he had collected 30 essays, which garnered 568 comments, with an average of 20 comments per essay.

The volume went from call for papers to a bound volume in one calendar year, a remarkable achievement for an academic book. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, another digital humanities scholar used Commentpress for her book Planned Obsolescence. Reflecting on this experience, Fitzpatrick writes that these new platforms are changing the way we think about publication, reading and peer review.

PEDAGOGY IS CHANGING, BECOMING MORE OPEN

Digital technologies are changing how we teach and making them more open. We think nothing of emailing students. Some faculty hold office hours through IM, Skype or Google HangOut. At many institutions, Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Blackboard & Moodle are commonplace. And, some professors are teaching in ways that are augmented by blogs and wikis. To the extent that these new technologies allow sociologists to reach a wider audience, these are also forms of public sociology.

In 2012, The New York Times declared it the “year of the ‘MOOC’.” MOOC is an acronym for Massive Open Online Course coined in 2008 by Dave Cormier, to describe an innovative approach to teaching that fostered connection and collaboration, and was intended to promote life-long learning and authentic networks that would extend beyond the end of the course.

MOOCs have garnered a lot of media attention in the mainstream press, and in the higher ed press, and there is even talk of revolution. This hyperbole surrounding MOOCs is both misguided and misplaced. What is perhaps most puzzling about all this is that there is nothing new, much less revolutionary, about the technology here. Some speculate that the attention is due to corporate players entering the field of online education, such as Coursera, which is backed by Venture Capitalists, and is partnering with elite academic institutions, like Stanford

Our own JustPublics@365 version of a MOOC, the POOC, is one that is participatory rather than massive and is closer to Dave Cormier’s original conceptualization. Our goal was to create something in keeping with the roots of CUNY as a public institutions, truly serving the public through education that’s open and available to everyone. We made sure that all the videos, the real-time livestream as well as the edited, archived videos were open to anyone that wanted to view them (without registration).

Likewise, we wanted to make all of the readings available to anyone that wanted to read them, even if they didn’t have a CUNY login and even if they weren’t registered for the course on our site. This sort of commitment to openness is one of the major distinctions between our efforts and the large, corporate MOOCs, which among other shortcomings, are not very “open.” As it turned out, making all these readings truly open turned out to be an enormous amount of work which fell on the shoulders of our heroic librarians.

We are still at the beginning of understanding how digital technologies will transform pedagogy in higher education, but it seems certain it has and it will continue to do so.

SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING IS CHANGING, NOT YET OPEN

Part of what’s changing about scholarly publishing has to do with changing views of copyright. It’s beyond my scope here to fully explore copyright, but Larry Lessig explains a great deal about copyright and how current laws don’t make sense in a digital environment in this TED talk. If you want to understand more about copyright, there’s no better place to start than with Lessig.

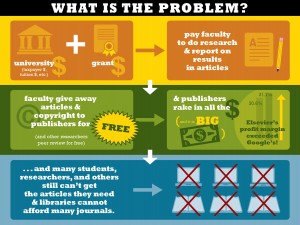

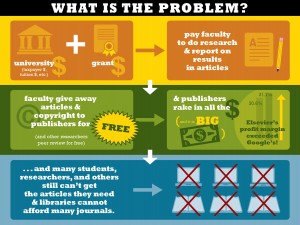

There is a lot wrong with academic publishing, much of it having to do with who holds the copyright to the work we produce, and more people are seeing that now. What’s wrong with scholarly publishing? This infographic explains it all.

(Image credit: Les Larue, Content credit: Jill Cirasella)

(Image credit: Les Larue, Content credit: Jill Cirasella)

The way the system of academic publishing is set up is this:

- Faculty are paid to do research & report results, then we

- Give away this writing and copyright to publishers.

- Publishers make HUGE profits, they do this by

- Selling our work back to libraries at enormous and rapidly increasing costs.

- Finally, the very often people who might benefit from reading our work can’t get to it because it’s locked behind a paywall.

As academics, we tend stash our research in places like JSTOR, where most people outside the Ivory Tower can’t get into. Some people have even begun to argue that it’s immoral to hide publications behind a paywall. A few scholars are marking a reasoned case for open access, such as Peter Suber’s book Open Access. Still others, like Jack Stilgoe, are simply dumbfounded at how stupid the system of academic publishing is.

HOW WE MEASURE SUCCESS IS CHANGING

All these changes in scholarship, pedagogy and publishing mean the ways we measure academic success are changing, too. We are shifting from 20th century ‘metrics’ to 21st century ‘altmetrics.’ So, for example, Jeff Jarvis (another CUNY colleague) has 123,667 Twitter followers. That’s a kind of “altmetric” – a measure of his reach and influence. Increasingly, book publishers, even some employers, look for evidence of your reach on particular platforms before awarding book contracts, even some jobs. This is less prevalent in academia, but it is on its way.

Not only are there new methods and ways of thinking about measuring impact, but it seems that old methods – like “citation counting” I described earlier with the SSCI – are broken. As the altmetrics site describes the situation:

“As the volume of academic literature explodes, scholars rely on filters to select the most relevant and significant sources from the rest. Unfortunately, scholarship’s main filters for importance are failing…”

So what are altmetrics? These are a “new, online scholarly tools allows us to make new filters; these altmetrics reflect the broad, rapid impact of scholarship …”

It might be useful to think about the way scholarship is changing in the digital era – as a shift from 20th c. models of creating “knowledge products” – to 21st century model of creating “knowledge streams.” With products – you count their impact once – with “knowledge streams” – you can also count various aspects of distribution – such as number of downloads, unique visitors to your blog, number of Twitter followers – which can have a much wider impact.

These new, digital knowledge streams (and measurement) don’t replace the “knowledge products” of traditional, legacy models of academia, rather they augment the traditional ones. For example, when you write submit a paper to traditional, peer-reviewed journal you want to think about optimizing the title of that paper for search engines. As another example, a peer-reviewed article that gets mentioned on Twitter will get more citations in the traditional peer-reviewed literature

LEGACY TO DIGITAL CHANGE IS PARTIAL

There is not a complete transition from a “legacy” past that is behind us, and a “digital” present or future. The legacy and the digital are imbricated, that is, they overlap in the here and now. This can play out in painful ways. For example, on tenure and review committees – where reviewers are tied to legacy models of academic scholarship and those up for promotion are engaging with digital models of scholarship.

A DIFFERENT SORT OF CHANGE: AUSTERITY

The politics of austerity mean that the funding landscape of higher education is changing. We are also living in a global (certainly US, UK + Western Europe) context of ‘austerity.’

(Image Source)

(Image Source)

Of course, ‘austerity’ is a convenient lie that says we’re out of money but reflects the reality of economic inequality and that the rich and super-rich will not invest in public goods and services.

Political attacks on higher education in the US are changing the landscape of funding. There is a Republican war on social science. Sen. Coburn managed to prohibit any monies for NSF-funded political science unless it was somehow “promoting national security or the economic interests of the United States.” He also tried to put the ax to NSF’s political science funds once before, but that failed in the short run, but in the longer run, the tighter definition allowed him to argue that the funds could exist, “as long as they weren’t squandered.”

There is a different political landscape in the UK, where there is an overall commitment to funding higher education. The Research Excellence Framework, or REF shapes these discussions in the UK. The REF means that the funding is tied to demonstrated “research excellence,” part of which relies on evidence of “impact” on wider publics.

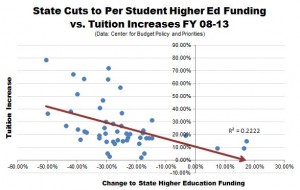

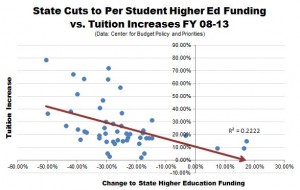

Back in the US there is no longer any broad commitment to funding state-funded public institutions of higher ed, at least when you look at data from state budgets, like this one from Georgia and this one that explores the overall trend in the US:

(Image from The Atlantic)

(Image from The Atlantic)

You really don’t need much more there than the dramatically, downward-pointing arrow to know that this means faculty have to be more entrepreneurial in securing their own funding for research (much like journalists are now considering ways to be entrepreneurial as a response to changing business model in news.)

And, of course, there’s very bad news in academia regarding the way we hire (or don’t hire) faculty. An estimated 73% to 76% of all instructional workforce in higher education are adjunct faculty.

Given the grim prospects for legacy tenure-track jobs in the academy, it is inevitable that many people with PhDs are going to do other things with those skills.

Increasingly, given the grim political economy of “austerity” and the many, many under-employed PhDs, I think that the affordances of digital technologies will create more and more entities like the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.

COMMERCE vs. DEMOCRACY

In academia, as elsewhere, we’re faced with competing forces of commercialization versus democratization as Robert Darnton, of DPLA noted in a recent talk at the Graduate Center.

The political economy of austerity, up to and including slashes in funding to public institutions of higher ed, the adjunctification of the academic workforce, and the attacks on funding such as the Coburn amendment, point to this broad conflict between forces of commercialization and forces of democratization.

Sometimes academics conflate the “commerce v. democracy “ struggle with the transformation from “legacy” to “digital” forms of scholarly communication, and I think this is unfortunate.

Given this context, what are academics to do to resist the forces of commercialization? I argue that owning the content of your own professional identity is key to this… For most faculty, their “web presence” is a page on a departmental website that they have no control over and cannot change or update even if they wanted to. “Reclaiming the web” means owning your own domain name and managing it yourself, a move Jim Groom has put forward for students and I argue should be the default strategy for faculty.

Too often academics, who are a contrarian lot, want to resist commercialization by refusing the digital. This refusal is misplaced and reflects a misunderstanding of the forces at play here.

Owning our own words, “reclaiming the web,” and our own professional identity online as well as offline is just one step.

Another step for academics, especially that handful with tenure, is to say “no” to publishing in places that don’t allow you to own your own work by retaining copyright.

A further step for academics, and especially for those in my discipline of sociology, is to use blogging to open up a space between research and journalism in ways that are creative, interesting, and contribute to an engaged citizenry.

In sum, the current state of affairs in higher ed looks something like this. On the one hand, we have the grim political economy of “austerity,” declining support for state-funded public education and attacks on other funding mechanisms like NSF. On the other hand, we have these amazing new opportunities to do our work in new ways, and make that work open to wider publics.

We are caught in the middle of the colliding forces of commercialization and democratization at the same time institutions of higher ed are making the transition from “legacy” to “digital” modes of operation.

Resisting digital scholarship in order to forestall the forces of commercialization is a mistake that too many academics make. Instead, we as academics need to embrace digital scholarship in ways that help foster democratization.