In the wake of any disaster, emergency response typically includes the American Red Cross, whose recognizable logo signifies a first stop for help. Volunteers respond quickly to set up communication centers, coordinate medical attention, arrange shelter for displaced people, provide food, and offer general support. This wide range of services requires tremendous coordination, which is particularly remarkable for an organization that is primarily staffed by volunteers. The explosion in East Harlem was no different. Red Cross volunteers went to work immediately and their work continued for a month afterward.

image source

image source

According to a follow up report on their blog:

- The Red Cross Emergency Operations Center was in operation and fully staffed 24/7 from the time of the collapse on March 12 through Sunday, March 23.

- More than 338 adults and children were comforted and assisted by Red Cross caseworkers at NYC resident service centers.

- More than 200 volunteers from across the Greater NY Region responded to the call to help those affected.

- Over 20,000 meals, snacks and beverages were served to residents and first responders.

- Between March 12 and March 14, more than 70 residents overnighted at the Red Cross operated shelter at the Salvation Army facility (for a total of 121 shelter stays; i.e., some of those 70 residents stayed more than one night).

- Dozens of children received solace and safe haven at the Red Cross shelter, with a little extra help from the Good Dog Foundation therapy dogs in conjunction with the ASPCA.

- Nearly 500 blankets and personal hygiene comfort kits containing soap, toothbrushes, face clothes, toothpaste, deodorant and additional items were distributed.

- Red Cross Client Assistance staff connected with over 20 families in need of mental health and/or physical health support.

One experienced volunteer, Mary O’Shaunessy, spoke to us at a community conversation held at the CUNY School of Public Health on April 26, which brought together residents and community groups to discuss what happened following the explosion and how to better prepare for future emergencies. She shared her experience following the disaster:

Community Conversations – Red Cross Volunteer Mary O’ Shaunessy

My name is Mary O’Shaunassey, I am a Response Manager for the American Red Cross of Greater New York. On the day of the explosion on Park Avenue, I was actually at work at my day job as a technology manager for a legal services organization that helps low income women.

As part of response management at the Red Cross, I receive four-hour reports on general activities. Regular fires, evacuations of unsafe apartments, and other small disasters. I received special messages from the Office of Emergency Management and the Red Cross management regarding this explosion. As soon as I could leave work at 5:30 or so, I headed to the Red Cross where we have an emergency operations center. This is an office that is staffed only during major disasters. There are 24 seats and each seat is occupied by a person with a very specific responsibility: for obtaining large quantities of food, for arranging the setup of a shelter, for arranging for licensed mental health professionals and physical health professionals to arrive at a scene, and so on.

My job as operations management was to make sure that each of those seats were filled or that each phone at each seat was being answered. So it boils down to there are 24 phones, if it rings, answer it, respond appropriately, make the right decision.

A lot of people don’t understand that the Red Cross is not a government agency. We are 90% of us volunteers. The volunteers that were available were people who are retired, self-employed, or unemployed. That can really limit our ability to respond to people who are linguistically isolated. Our volunteers speak what they speak, they’re available when they’re available. We happen to be lucky that a couple of our people were native Spanish speakers. It is possible that at a fire you can have people that are so linguistically isolated that no one can help them. We have facilities for that, but it takes some time to set up.

When I arrived at the emergency response center, I found it in full swing. People were already at the blast site. They were already working on a reception center. Until we have the capability, that is, a released building from the Board of Education, a custodian, and shelter staff, we have reception centers. And that’s where clients — and I have to define the word client here — we never call people victims because part of the Red Cross role is to encourage people in recovery and calling people victims does not encourage that. We have clients, and we have survivors. Clients, survivors, and family members were already at the site looking for information.

The definition of a disaster is that it is unplanned, therefore information is always partial, immediate, and changeable. It’s very difficult to set and manage expectations. We are also committed, individually, corporately, and internationally to client confidentiality. It is very common for family members to call, and we were getting these calls, and people saying “my sister-in-law was there, my nephew was there, my cousin was there.” We cannot release that information. We did not have the information about the deceased but even if we had it, we cannot. We cannot give information about who is registered at a reception center, or a shelter. What would happen if a man were to come and say my “wife is there, I need to get to my wife” and we released that information and that woman had an order of protection against an abusive spouse. That’s something that we always have to protect people against. We cannot make assumptions about what people are telling us.

Most people are honest. Most people want to help. We have to be realistic, as well as optimistic in our view of human nature. So we were getting calls from volunteers, we were getting calls from partner agencies, we were getting requests for food. We try to purchase food from local vendors. We try to purchase all our supplies from local vendors. Surviving vendors may have decreased foot traffic. They may have decreased customer assistance because their customers have been displaced. By the Red Cross spending money in these local businesses, we’re keeping these small businesses in business. We’re keeping their employees able to contribute to the community and therefore the function of the society is continuing to go.

Very often we get complaints from people who say “I didn’t want my money to do go overhead.” Overhead is very interesting. If you think about wanting a report about where money goes, you would say “yes I want a report.” A report needs a database, a list of expenses, and a list of donations. That computer needs electricity. The person who is putting that information in needs an office with electricity, running water, and maybe heat or air conditioning. The software needs to be purchased. That’s overhead. So it’s very interesting to try to explain what overhead means in terms of how people get their wishes in terms of donations.

We have overhead and we are not ashamed of that. We are very careful about donor dollars. In order for a Red Cross responder to go out by themselves, that is, to respond to a fire or a vacate, they have extensive training and extensive practice, and they undergo a background check. When I walk out to a fire, I can have as many as 30 debit cards, with a maximum value in the field of $1,000. If I’m handing someone, as a manager, $30,000 nominally in debit cards, I want to know who they are. That is why what we call spontaneous volunteers get asked to do really basic things: hand out water, hand out food. Trained responders go into people’s homes. We go into homes to evaluate damage, to determine how much cash assistance to give, whether to give hotel rooms. I would not want someone in my home that had not undergone a background check.

So these are the things that go into being a Red Cross responder. And it all gets really ramped up in the event of a large disaster. As you gain experience, it’s also important to know how to step back. I’ve been a volunteer for 7 years, I’m very experienced, and now I’m in management. I have to step back and allow other people to learn how to do this. That can be hard because they’re training and by definition, trainees make mistakes. Sometimes, in an event like this, a simple mistake can get very high profile very quickly, and it’s very difficult to manage. We never send trainees out alone, but in a fast-moving, crowded event, they make decisions. Sometimes they’re very good decisions and sometimes they could have been better. And we work on that in what we call hotflashes. After an event, and in some cases after every 24 to 48 hour period, we sit down together and figure out what went wrong, what went right, and how to keep doing what was right, and how to correct what was wrong. It’s a continuous process.

I love volunteering for the Red Cross. I like going out, I like adulation, I like people saying “oh you do wonderful things.” It’s an ego charge, and I’ll take that. Fires, disasters are an adrenaline charge, but you also have to balance that against the needs of the organization and the needs of the community. Those needs will go on long after I am able to respond to disasters.

This eBook, the fourth in our series, deepens and expands the work of a community meeting at the CUNY School of Public Health on April 26, 2014. This meeting brought together volunteers, city officials, and faculty and staff from CUNY to discuss emergency response following a tragic gas explosion nearby that had killed 8 people the previous month. Participants met in groups to discuss the event, make recommendations for better emergency response in the future, and strengthen community partnerships. Afterwards, several people sat down with us to talk about their experience, which we produced as a series of podcasts.

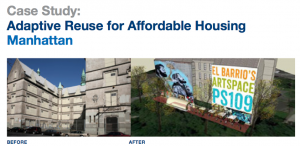

This eBook, the fourth in our series, deepens and expands the work of a community meeting at the CUNY School of Public Health on April 26, 2014. This meeting brought together volunteers, city officials, and faculty and staff from CUNY to discuss emergency response following a tragic gas explosion nearby that had killed 8 people the previous month. Participants met in groups to discuss the event, make recommendations for better emergency response in the future, and strengthen community partnerships. Afterwards, several people sat down with us to talk about their experience, which we produced as a series of podcasts. This series portrays only a small portion of the dynamic activist work being done by local residents. To do justice to this rich community would take far longer. Luckily, this work is represented by the many community groups that are active in East Harlem and in everyday life in the neighborhood. We encourage you to start here and do more exploring on your own, both virtually and in person. Take a walk around the neighborhood and meet some of the amazing people who call it El Barrio.

This series portrays only a small portion of the dynamic activist work being done by local residents. To do justice to this rich community would take far longer. Luckily, this work is represented by the many community groups that are active in East Harlem and in everyday life in the neighborhood. We encourage you to start here and do more exploring on your own, both virtually and in person. Take a walk around the neighborhood and meet some of the amazing people who call it El Barrio.