For most people, the web is now a constant part of our daily interactions. Yet, most of us understand little about how digital technologies are changing the personal, social and political aspects of life on a broad scale. At the University of Maryland-College Park, sociology graduate students, PJ Rey and Nathan Jurgenson, have come together to examine how the web and digital technologies are changing our society, economy and culture.

Student-led conferences that are open to those beyond tight-knit academic circles are almost unheard of, and yet PJ and Nathan are pushing the norm. Using gender, race, class, age, sexual orientation, and disability lenses, PJ and Nathan have organized an innovative conference that “bring(s) together an inter/non disciplinary group of scholars, journalists, artists, and commentators” to theorize the web. Together they are building a model of tech-driven social transformations.

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing PJ and Nathan about Theorizing The Web (#TtW13) which launches today at the Graduate Center as part of the JustPublics@365 Summit: Reimagining Scholarly Communication in the 21st Century. The conference runs all day Saturday, 3/2 on the Concourse Level of the Graduate Center. It’s open to all, and registration is required (and you’ll need photo ID to get into the building).

JustPublics@365: Can you tell us a bit about how the first Theorizing the Web conference started?

NJ: It started in frustration. PJ and I were beginning as sociology graduate students at the University of Maryland applying social theory to new technologies and went to conferences that bummed us out in a few specific ways. It was tough to get theory people to talk about the Internet and even more difficult to get the tech-researchers to take seriously theorizing, especially that which isn’t strictly instrumental. Where were the critical theories of the Web taking deeply into account the intersections of power and domination? the dangers of capitalism? critical-race, feminist, queer, post-structural, postmodern, and so on?

These were the ideas we wanted to immerse ourselves into and we wanted to find the right network of people. We had already jumped onto social media to find people. We created the Cyborgology Blog. And it was PJ who first came up with the idea of maybe hosting a small group of graduate students working on similar ideas since he had done that in his Philosophy department years ago.

PJ: Right, our goal was really to build community that we didn’t find ready-made elsewhere. We didn’t have many resources to throw a conference, but our sociology department at the University of Maryland had plenty of space available, so we figured would could put something together in a very DIY fashion and attract a few dozen people who were also passionate in thinking theoretically about digital media, particularly from a social justice bent. We basically just made a list of all the things that would make us most excited about a conference, tried to build them into our plans, and hoped people would show up. We thought an exciting conference would try to get past the jargon and focus on ideas important to a wide audience. We also thought it would be good to engage artists and to make things really fun having socials with bands and djs.

From the earliest stages of our planning, we thought it would be fantastic to have danah boyd give a talk because her willingness to engage a wide range of audiences and her focus on issues of public concern really seemed to fit the spirit of our conference well. From the moment we contacted her, she was so generous and wonderful in helping us pull things together for that first year. I really couldn’t imagine having had a better keynote to launch this whole project. Also, in the same year, Saskia Sassen contacted us after hearing what we were planning and offered to travel down to Maryland to join us and has been hugely supportive ever since. Having talks by both danah and Saskia, as well also our advisor, George Ritzer (who, also, unfailingly offers the best suggestions on tough planning decisions), really set the tone for the first event, and, frankly, just got us both super-psyched about the whole thing.

Personally, that first conference introduced me to a number of extraordinary people with whom I now regularly collaborate. For me, these relationships were the primary motivator in turning this original conference into an annual event.

JustPublics@365: Isn’t it a little unusual for graduate students to start a conference that’s not just for other grad students?

PJR: Originally, we just sort of assumed that Theorizing the Web would be a graduate-student conference. In fact, that’s how we we framed it in our initial proposal to the Maryland sociology department. Reeve Vanneman, the sociology chair at that time–who really helped get us on our feet–encouraged us to open it up to faculty too, since there was really no reason to turn away anyone interested in the topics we wanted to address. As it turns out, a lot of faculty–even senior faculty–were deeply interested in theorizing how digital technologies were both shaped by and shaping society. In fact, we received far more submissions than we anticipated. The main difficulty for us, as grad students, is that we can only feasibly organize a relatively small conference (everyone including the speakers volunteer their time and energy). So, this means we end up being forced to turn away a lot of really great submissions. Hopefully, more events will continue to develop to serve the apparent demand for the kinds of conversation that Theorizing the Web and similar events facilitate.

NJ: And as we move forward into planning for 2014, we are looking at ways to expand the conference to meet the demand, which we are simply not able to do right now. We also are looking into expanding who makes the submission decisions beyond just ourselves, something that now seems appropriate given the surprising growth of the event.

Most importantly, we could not have done the conference those first two years without the help of fellow Maryland graduate students, Tyler Crabb, Dan Greene, Rachel Guo, Zach Richer, Jillet Sam, David Strohecker, Sarah Wanenchak, Matthias Wasser, and William Yagatich. Tyler and Sarah are again helping us this year, along with two more graduate students, Whitney Erin Boesel and Tanya Lokot, who have gone above and beyond in helping to make this event happen. JustPublics@365: So, 2013 is the first year that Theorizing The Web is in New York City. How do you anticipate that this will change the conference?

PJR: We’ve teamed up with brilliant folks at JustPublics@365 who helped reinforce our emphasis on engaging broad publics and important social issues. This partnership actually has some deep roots. Jessie Daniels helped us get Theorizing the Web off the ground by organizing a really excellent panel on race and social media at our first conference. We’re both fans of her scholarship on cyberracism, which is a perfect fit for Theorizing the Web. She introduced us to Bronwyn Dobchuk-Land, Jen Jack Gieseking, Matthew K. Gold, Wilneida Negrón, Morgane Richardson, and Emily Sherwood. Having this great contingent of CUNY folks each contributing their unique talents to the planning of the conference helped to give to give TtW13 a distinctly NYC flair. Also, we’re really excited to have an invited panel that specifically features research on the Web being done at the CUNY Graduate Center.

NJ: Agreed! One of the goals Theorizing the Web has had is to make ideas more public. The space should be open to the public (the conference registration has always been pay-what-you-can), we’ve deeply integrated the Twitter conversation and now the live stream, and we’ve also pushed and selecting for ideas to be addressed in a way that is appropriate not just for an inter-disciplinary audience but also one that may be non-disciplinary. Moving the event to New York City is helping us reach more people since there are more people working in these areas as researchers, artists, activists, and so on. For instance, there is an #OccupyData hackathon happening concurrent with the conference in the James Gallery, and the New York City-based culture mag The New Inquiry, who we’re huge fans of, is helping us promote the event outside of academic circles.

JustPublics@365: The conference is, obviously, about ‘theorizing’ the web – but how will people be ‘using’ the web during the conference?

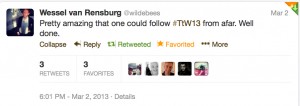

PJR: We really try to practice what we preach with the conference: namely, getting away from the “digital dualist” conception of online and offline as separate spaces for social interaction. We set out to “augment” the conference with digital media, which we believe helps us reach the widest possible audience. We offer live streaming video of all our panels so that folks who cannot afford a plane ticket to travel to the event can still watch in real time. Even more important, we actively work to move the so-called “Twitter backchannel” onto the front stage by having “hashtag moderators” at each panel who livetweet the discussion and ask the panelists questions on behalf of those viewing the panels remotely. These tactics are aimed at making anyone who cannot be physically present still feel like a full participant in the event and also at making the role of audience member a less passive, more “prosumptive” experience. That is, after all, what social media is all about!

NJ: An example of the culture of digital-material enmeshment at Theorizing the Web was the 2012 keynote, a conversation between NPR’s Twitter journalist Andy Carvin and UNC Sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, namely, Zeynep’s superhuman ability to follow the discussion face-to-face together with the very, very active Twitter feed. I think there were about 5,000 tweets that day on the conference hashtag and we were even the #2 trending Washington D.C. topic at one point when I checked. Meanwhile, Zeynep navigated the simultaneity of the various flavors of information coming at her with ease. Tellingly, when Zeynep asked for questions, the hands in the room didn’t go up, instead, they collectively checked Twitter. JustPublics@365: Can you say a little about how the Friday evening event is different from the conference on Saturday?

PJR: Friday features a set of invited speakers we think will be of broad interest to our audience. We know a lot of people will be just arriving on Friday and many will be doing last minute preparations for Saturday presentations, so we wanted to keep the Friday event pretty simple. Saturday features 3 sets of concurrent panels, each focused on specific issues. It’s pretty packed schedule with 48 total presentations and a closing keynote by David Lyon.

This is actually the 7th conference I’ve helped organize now. And, above all, I’ve learned that meeting and catching up with people is the part that conference-goers look forward to most. So, on both days, we try to provide as much opportunity for socializing as possible, while still cramming in lots of great discussion. We really hope everyone can make it to the Friday night social and the Saturday night afterparty.

NJ: We think it is fitting to open the conference with a plenary on Surveillance by Alice Marwick, which is a real juxtaposition to the closing keynote, also on surveillance. We hope attendees appreciate Marwick’s somewhat-different approach to surveillance, namely, her conceptualization of “social surveillance” that differs from traditional surveillance studies to capture the rise of social media. Next, the invited panel titled “Free Speech for Whom?” should be a lot of fun. danah and Zeynep are leaders in this line of inquiry and are well-known to most of our audience. Adrian Chen is a journalist at Gawker and wrote the article outing (aka, “doxxing”) that nasty Reddit troll, which was pretty big news and should provide a new angle. We also reached out to some folks who are more unabashedly ‘information-should-always-be-free’, but timing unfortunately didn’t work out. [note: Kate Crawford was originally on this panel but had to back out because of a conflict with another conference she is keynote-ing]. Last, we’re especially excited to have an event in the James Gallery, as art has always been central in our thinking of these issues. JustPublics@365: Right, there seems to be some effort to involve artists. What’s that got to do with ‘theorizing the web’?

NJ: Marshall McLuhan liked to say that only artists can know the present, while, at best, the rest of us are in the near-past. I’ve always found it interesting how, contrary to what McLuhan would have wanted, art and academia are so often separated. Academics, at least in the social sciences but often beyond, rarely consider art as of equal epistemic standing to their research; that is, it isn’t equally legitimate or able to convey ideas, insights, truths (what Lyotard or Foucault might talk about as subjugated knowledges). Meanwhile, artists are often engaging cutting-edge theoretical topics, and my hope is that academics can learn from them. And perhaps the artists can benefit from the academic skill of translating the ideas for different audiences and linking the insights to other theories, research, histories, and current events. And I can’t speak of art too long without thanking the great design work we’ve been fortunate to have with this conference, Ned Drummond for 2011 and 2012, and Imp Kerr for 2013. We owe both a large debt of gratitude.

JustPublics@365: What are you most looking forward to about #TtW13?

NJ: Seeing people meeting new people, making that new connection, and striking up conversation and spinning off new ideas. Also, seeing people taking notes and tweeting ideas during the talks. And, selfishly, getting to see all those friends we’ve made through the conference, Cyborgology, and Twitter. There are those friends and colleagues I do not get to see often, and what is also exciting is meeting people in-person I have previously known only as a Twitter-handle or a name on a journal article. Oh, also, the conference after-party on Saturday night! We have a DJ (Sean Gray of Fan Death Records) and a band, Niabi, who is an excellent ambient-meets-dreampop-meets-shoegaze electronic musician.

PJR: Meeting and catching up with people is always the most exciting part for me too. And, really, that’s why we started this whole thing in the first place. I often reflect on how many of my close collaborators I’ve met through the Theorizing the Web and how different my life would be if we hadn’t started the conference. There are a several folks who I first connected up with in 2011 and who keep coming back with new and exciting observations. Also, I’m excited to be exposed to new voices and new ideas. After the event, I’ll go back and watch the archived video of all the panels I missed. The past conferences gave me so much to think about that it took a month or two to fully digest.

JustPublics@365: Can people still participate? How do they go about doing that?

PJR: The program is set at this point, but as I said before, no one at Theorizing the Web is just a passive viewer. Lively conversations have already begun on the #TtW13 hashtag and on the Cyborgology Blog. We invite anyone and everyone to jump in. Your questions, whether asked in-person or through the hashtag, will shape the conversation at the event. I’m really looking forward to seeing what emerges as the main talking points.

NJ: And we invite those inspired by what happens at the conference to write about it! The Cyborgology blog often hosts guest-posts on these topics and is a great way to “keep the conversation going”, as Richard Rorty might say.

Nathan Jurgenson(@nathanjurgenson) is a social media theorist, PhD student in sociology at the University of Maryland, musician, photographer, and co-founder of the Cyborgology blog and Theorizing the Web conference. PJ Rey (@pjrey) is a PhD student in sociology at the University of Maryland examining how social media is changing our economy and culture. In addition to being a co-chair of the Theorizing the Web conference, he is also a co-founder and editor of the Cyborgology blog.

Mark Halsey, “A Short History of Modernist Painting” (1982)

Mark Halsey, “A Short History of Modernist Painting” (1982)