This past week, I interviewed Alondra Nelson, PhD (Professor of Sociology and Director, Institute for Research on Women and Gender at Columbia University), about her research on the Black Panther Party, which culminated in her most recent book Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. In this interview, I ask Professor Nelson about her experience entering spaces more commonly trodden by activists, what role she thinks stigma has in criminalization and public health, and the problems she sees with medicalizing behavior.

Can you share a bit about how your research speaks to issues of criminalization and public health?

I guess I set out to study public health, in a sense, but certainly not criminalization. In the process of writing my last book “Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination,” I discovered while doing that research that members of the Black Panther Party were involved in a legal campaign, an activist campaign, to block funding to a proposed research center at UCLA in the early 1970s, 1972 specifically. This center was to be called The Center for the Study and Reduction of Violence, and it was being proposed at a time where there was a lot of public anxiety and public discourse around violence in American society. It was a time during which the covers of Time magazine and Life magazine were posing the question “What are we going to do about this scourge of violence in our society?” One of the answers that arises, or response to this moral panic, is this proposal for this center at UCLA.

The center is interesting for a couple of reasons. One, that I don’t delve in too much into in the book but is worth noting in our conversation, is that the Center is being proposed underneath the umbrella of Neuropsychiatric Institute at UCLA, which still exists, and it’s at a moment where psychologists and psychiatrists are in effect working to make their disciplines more scientific. Now, it’s common place for a colleague in psychology departments to do research using MRI, and these sorts things it was uncommon. It was a moment in the evolution of psychology and psychiatry that it was becoming more scientific. Part of how it was becoming more scientific at this UCLA project is that they were looking almost solely to biological and physiological causes for violent behavior. They were looking at endocrine levels. They were looking at genes. They were doing a proposed study that was going to look into violence in the XYY chromosome. There’s a study that was proposed to look at, the hypothesis was “are women more or less violent at different moments in their menstrual cycle.” There were a couple of proposals that began from the assumption that Black and Latino boys and men were biologically prone to be violent. It was criminalizing in two ways. One the one hand, it assumed that there were two kind of pools (there are lots of different research project that would have been housed in this violence center, but one of the projects was planning to look at populations to test prisoners, primarily Black and Brown prisoners, to see if there was something effectively wrong with their brains; if there was brain pathology that was why they were violent. These were people who were already incarcerated and institutionalized, so the assumption there was that there was a link between biology, brain pathology, and violence.

On the other hand, there was another study that proposed to look at Black and Brown boys in the Los Angeles public school district with the implication being that these boys were on their way to being criminals. So, can we intervene? Let’s look at their brains before things go bad, or maybe they’re just natural born criminals and things will already go bad. The interesting thing is that at least some of these research projects are obviously about ideas about who are criminals, who are natural born criminals, in a way that goes back to Lambroso in the 19th century, this idea that some people are inherently bad seeds. On the other hand, and this goes to the public health piece, it was articulated in the proposal in a train around health care and health issues, wanting a healthier society and that the justification for doing it was more social health and social well-being.

How has criminalization and mass incarceration affected the lives of people in your research?

My research has been among, this for this book in particular, both health activists who are professionals and health activists who are lay experts or lay people. It’s less the health piece, but it’s more that they’re activists that have led to criminalization and mass incarceration being significant parts of their lives.

I write about the Black Panther Party. As we know from the historical record, as we know from the media and the like, that the federal government, the US Government, made it it’s mission to really decimate the Black Panther Party’s ranks. The counter-intelligence program, COINTELPRO, went about the work of decimating the ranks of the Black Panther Party and really just diminishing their spirit through many means. They planted news stories and they shaped public perception about the party. One of the things that people often ask me is “Why haven’t we heard any of this stuff about the Black Panther Party’s self-activism?” One of the answers I suggest is that the COINTELPRO was successful in shaping media frame around the Panthers even for those who might have been sympathetic. The federal government’s work of framing the party also did the work of shaping our national memory of them.

There’s that piece. Part of it was also that, under the banner of then-governor Reagan being a law-and-order governor and a backlash to the activism of the 60’s, there was a, effectively, war on activists although it was never named. We had the war on cancer and we had the war on poverty, but there was certainly also a war on activists.

This meant that many of the people who were involved in the Black Panther Party and other activist organizations from the time went to jail on trumped up charges or went to jail perhaps on legitimate charges, but served or continued to serve disproportionate sentences. People have been in jail or in solitary confinement for crimes that they were convicted of in a legal process that somewhat questionable for 30, 40 years. One of the legacies of the Black Panther Party and the way that they responded happens in this cauldron of expansion of mass incarceration and the criminalization of activism as an excuse for doing that.

Just to give you an example of how things have changed in the last 4 decades or so, the activists that I write about would basically set up a storefront health clinics, for example, or they would set up the headquarters of Black Panther offices at storefronts. These sorts of things. People ask me now, “Could they do this now?” The only legacy of this work that was able to continue on in the same way, although there’s lots of legacies of the Black Panthers self-activism, is the Common Ground Health Clinic that springs up after Hurricane Katrina. I argue that the only reason that it was even able to happen is because the entire health care and criminal justice infrastructure of the city had completely collapsed.

The Common Ground Health Clinic was started by a former Black Panther, and a nurse, and another activist. Three days after Hurricane Katrina comes through, but within 6 months, the Common Ground Health Clinic had become an NGO. There was a lot of pressure from both state and federal agencies for them to get licensing and these sorts of things. So, for the most part, the Black Panther activism that I write about, worked against the grain of being public health authorities. They actually resisted and rejected any effort for them, for the most part, to get licensing and accreditation from local or state agencies. There was certainly the place in Chicago where there was a series of lawsuits that was trying to get the Black Panthers to go to be under the auspices of the public health authority in that city.

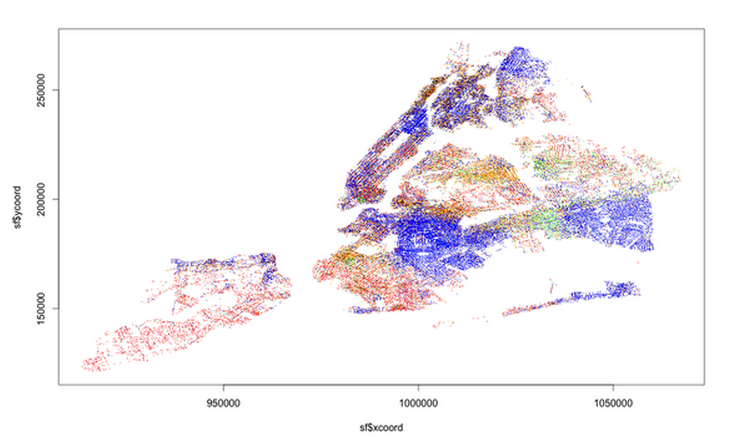

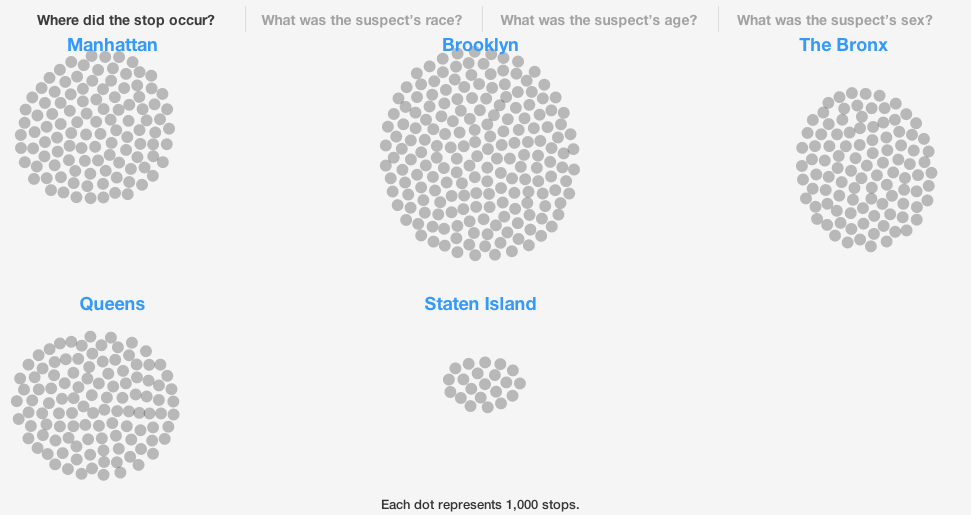

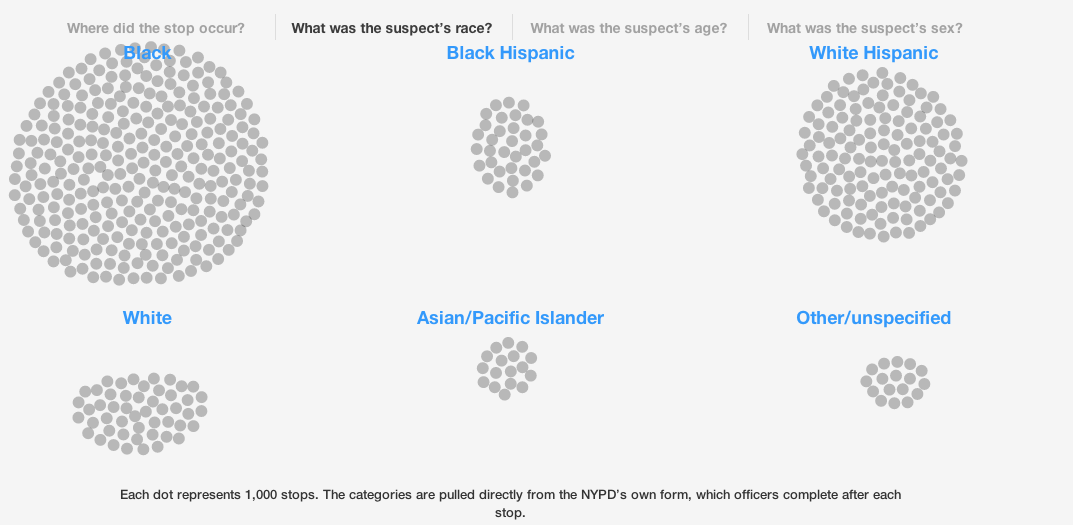

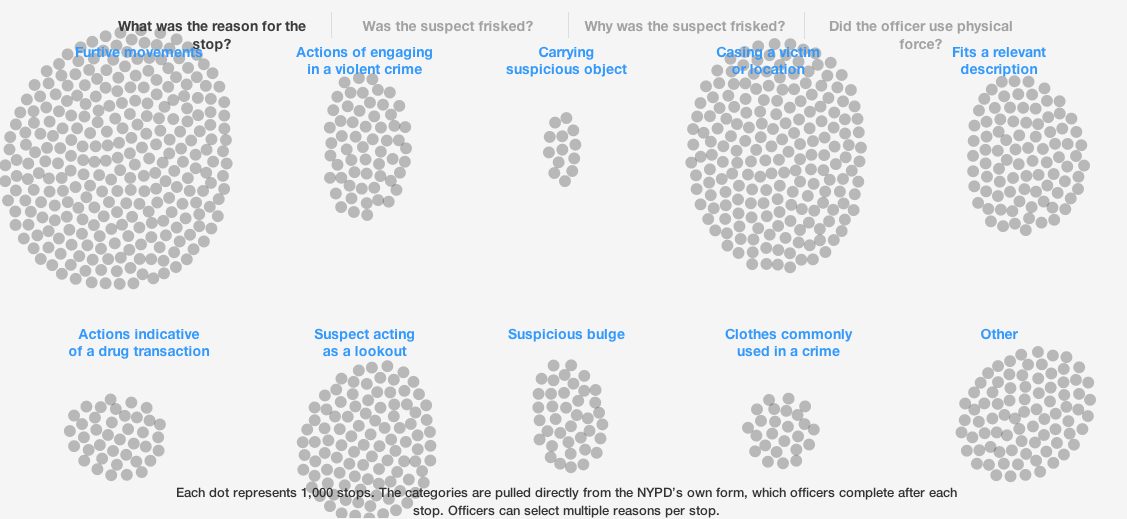

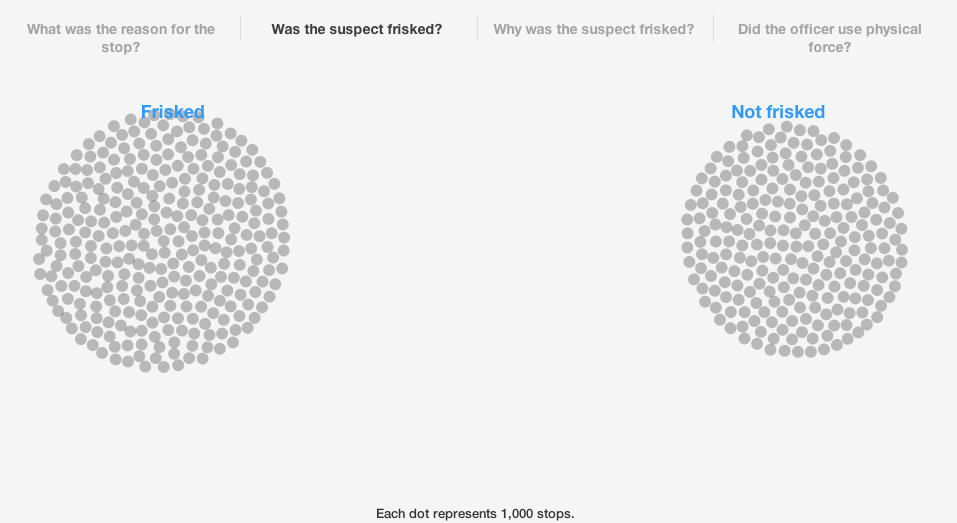

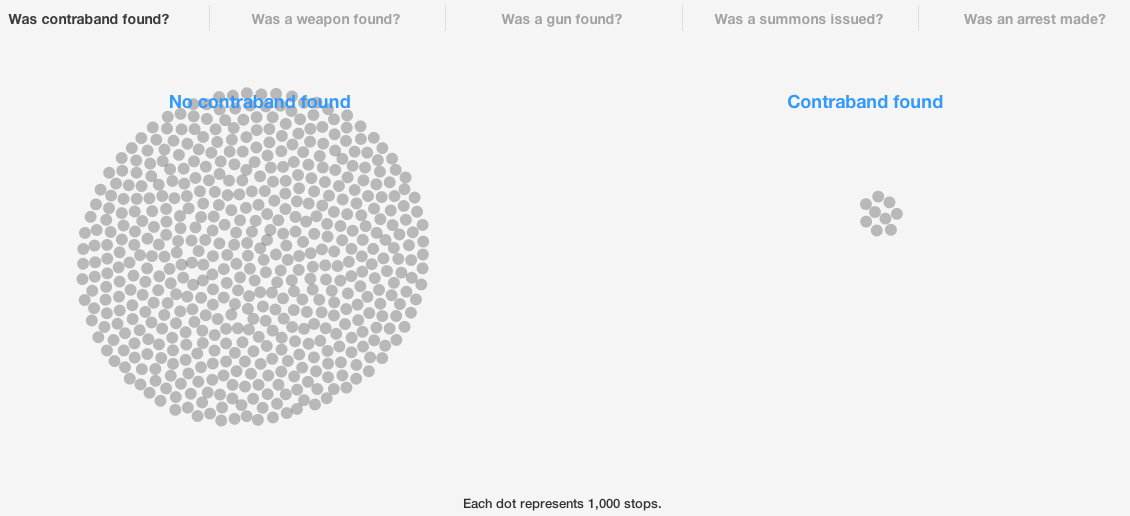

But what happens now? The Hurricane Katrina Common Ground Collective Clinic is, I think, anomalous because Hurricane Katrina, a natural and unnatural disaster, was a bit anomalous. You couldn’t pull this work off today because if you open a storefront clinic, it would be shut down by police authorities in a day or two. I don’t think could make a go of it. I think one of the enduring legacies of this criminalization of activism is (just to look at activism at a place in New York City today); I participated, for example, last March and our colleague Jessie Daniels was there as well. I was there with her in the silent March against stop and frisk practices in New York City. That was up and down along parts of Fifth Avenue.

In order to pull off that March, the activists had to go to City Hall. They had to file a permit. They had to get permission from the state. They had to tell the mayor’s office or the police department between which blocks they would walk on Fifth Avenue. They had to tell the mayor’s office and the police department at which times the protest would take place. That creates a different kind of activism. Could you imagine if during the civil rights movement, you had to go to Bull Connor, a notorious racist police officer, and tell him that you’re going to do a sit-in between these days or you’re going to hold a March at this time between these days. It would have been impossible. But because one of the responses to the population of activists that I studied in the 60’s and 70’s has been the criminalization of activism, we no longer can even imagine organic activism excepting the Occupy movement in recent years.

I’m going to throw 3 questions at you. What are your thoughts on policy approaches that draw from public health rather than criminal justice? Are there any examples of policy approaches that draw from public health rather than criminal justice? If so, do you think these are better or just reproduce the same systems of inequality?

Those are tough questions I think because it depends on the population. In Sociology, Peter Conrad, among others, have developed and elaborated this idea of medicalization. In a classic book Peter Conrad and his coauthor write about the process of medicalization moving a behavior or a condition from the category of sin or stigma to illness. That illness allows people to take what a person would call a social role. It allows people to sometimes get sympathy and get resources. There’s a whole suite of social actions that come into play when someone is identified as having an illness and being a patient and being more sympathetic.

I think that to put something in a public health frame rather than a criminal frame ideally allows this to happen for people. If someone is a drug addict and struggling with drug addiction, ideally for us to say as a society and as physicians and activists, this type of person is suffering with a disease and we shouldn’t stigmatize the behavior. We need to use the whole apparatus of public health resources to help this person.

The classic medicalization story is alcoholism. Alcoholism going from being a crime or a sin to being a condition where people can say “I’m an alcoholic” and they’re in that healing process and these sorts of things. However, and I argue this a little bit in the Panther book when talking about health issues, I think if a population is already so deeply stigmatized like particularly poor African-Americans and poor African-American males so that they’re almost like a caste in thinking about the lack of social mobility in India. The shift from criminalization to medicalization doesn’t offer that transition that I’m talking about necessarily.

For some poor, marginalized population, they’re so over-determined by criminal stigma and racism, effectively, that that window, that threshold to medicalization that might offer public support, resources, sympathy, a new social role is not available to them. I think that, and this is going to end our conversation on a down note, but the down note is to just accept that that’s true and not look to the public health arena as the panacea for social progress. I just think there are, fundamentally, groups for whom medicalization doesn’t work in the same way.

We need to work on the bigger issue of stigma. If you have a group of people who are like a caste; who are considered subhuman, a-human, always criminal, beyond help, undeserving; the move to a public health frame alone is not going to work. I think that that can be part of the piece, the move from criminalization to public health, but the larger work needs to be around a human rights struggle that awakens the awareness and the humanity of all of us.

A major focus of JustPublics@365 is bringing together academics, activists and journalists in ways that promote social justice, civic engagement and greater democracy. What sort of ‘lessons learned’ do you have from your experience entering a terrain more frequently trod by activists and journalists?

I think one answer comes out of my research and one that comes out of my experience working with JustPublics@365. As a researcher I learned that the way that we as a society treat activists, and treated this activist population that I worked with in particular, has consequences for what we can know about the world. It took me a very long time to have access to some of the people that I have interviews with in my book, in part because they have been so mistreated by other researchers; they had been so mistreated by other forms of authority: police authority, physicians. As a researcher, I couldn’t just go in and say, “I’m a young professor at Yale. Let me interview you.”

Most other places in the world, if you say “I’m professor XY from XY of the institution, that opens doors for you.”. But in activist circles, that often closes doors. What that meant is that I had to build long-term, sustained, still-existing-today relationships with the people I wanted to speak with for my book. These had to become more than just me parachuting down, extracting information and resources, and parachuting out.

These were long conversations that continue on. I’ve been happy to receive feedback about my book from the people I’ve spoke with and receive feedback from them. I think that’s one lesson. One lesson is that the structural balances in society are what they are. I know enough not to say that my structural relationship with working class activists is equal. We’re not equal in that way, but to the extent that we can try to have egalitarian relationships with the people that we work with, we need to try to do that.

I think organizations like the Panther Party offered really interesting ways for thinking about that. By necessity, they had to collaborate with doctors and nurses, nursing students, medical students to do their clinics. They didn’t have enough manpower or expertise to pull off a nationwide network of health clinics by their own, but they vetted everyone who worked with them. You couldn’t just come in and say, “Oh, I’m a medical resident at Harvard. Let me come and work in your clinic.” The party wanted to know what your political aspirations were, what your theory of social justice was. They wanted to know if you had read Franz Fanon, if you had read John Hope Franklin, if you had read Malcolm X, and often demanded that you do so. I think that we need to think about these as wholesome relationships that come with responsibilities and obligations on all sides.

More recently, I had the opportunity to participate on a panel that sets public health with Lillian Guerra, whose an editor at The Nation, gabriel Sayegh from the Drug Policy Alliance, and Glenn Martin who’s from an organization for formally incarcerated folks. I wasn’t sure, sitting down with these people who do work that’s a lot more contemporary, where the Black Panther piece would fit, but the round table (you’re never sure how these things are going to turn out when people are speaking, in some ways, informally), was very enlightening.

It was really challenging me to think about what this historical story meant for now. I think as scholars, you don’t have to justify why a historical work matters. We inherently think as scholars that a type of work that tells a new story or allows us to see the world anew, has inherent value. I think sitting in a conversation with two activists and a journalist really forced me to think of the “now” of the project.

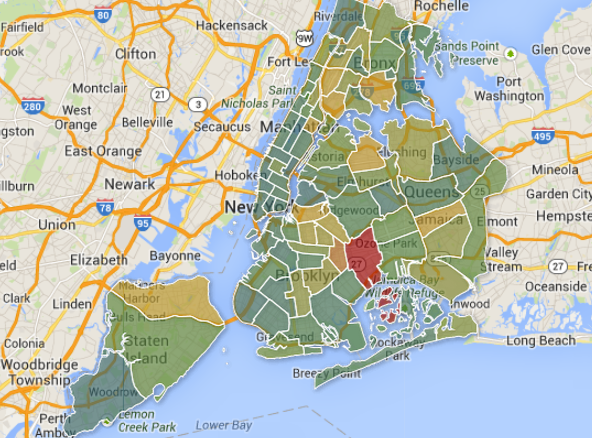

The criminalization of activism now, that we talked about previously, that would make it impossible to have an organization like the Black Panthers to do the health activist work that they were doing, to do it now. Or to think about all that has changed with regard to the full-scaling up of mass incarceration in such a way that you might not even have in-community enough people and leadership to sustain the activist communities that you did 40 years ago.

For me, as a researcher-scholar-activist, the most important takeaway from that experience was to always, not in a present tense sense, everything from the past doesn’t have some residence in the present, but to think about those places where it does and where the work can be used in the presence of making a better world today.

***

This post is part of the Monthly Social Justice Topic Series on From Punishment To Public Health (P2PH). If you have any questions, research that you would like to share related to P2PH or are interested in being interviewed for the series, please contact Morgane Richardson at [email protected] with the subject line, “Stop-and-Frisk Series.”